Research and development project results are useful sources of up-to-date information, but often feebly used because of the inadequate or poor dissemination of results. This paper is a case study of a participatory student workshop on crisis management and conflict prevention that utilized the contemporary results of IECEU-project (”Improving the Effectiveness of Capabilities in EU Conflict Prevention”). The case study illustrates how to implement project results in an agile and participatory way to university students.

The Finnish Defence Forces International Centre (FINCENT) and Laurea University of Applied Sciences (Laurea) organized a pilot workshop “Understanding the Conflict in Central African Republic” in Crisis Management NOW event organized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs 17th of May in Helsinki, Finland.

Workshop brought together experts and university students interested in conflict management, peacebuilding and crisis management. The workshop integrated the research findings into practice in an innovative way by establishing an interactive environment for participants to build conflict analysis capacities and to gain basic terms and understanding of crisis management concepts.

The material of the workshop was based on the EU Horizon 2020 IECEU-research project and more specifically on the deliverable 3.3. Central African Republic research report results (IECEU 2017). Case study highlighted the historical context of the conflict, and the attempts to end the crisis and/or restore peace by means of crisis management.

1. Co-design process of the workshop

The workshop was initially designed and implemented in collaboration with representatives of student organizations from five different universities (University of Turku, University of Helsinki, University of Lapland, University of Tampere and the National Defense University).

The workshop was based on end-user centered approach. It was crucial to embrace participants as the “customers” in the planning phase of the workshop. As the representatives of participants alongside with Laurea and FINCENT were all engaged in the design process, it is convenient to describe the process as “co-design” rather than with a more popular term “co-creation”. In a co-creation process, the facilitator does not normally actively take part in the design but enables the participants to work by themselves. In co-design the facilitator takes actively part in the design process (Holmlid, Mattelmäki, Sleeswijk and Vaajakallio, 2015)

After the initial contacts with the student organizations, a planning group was formed. Group met several times to brainstorm the initial idea and execution of the workshop. Representatives from Laurea and FINCENT also acted as the messengers between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs planning committee of the whole Crisis Management NOW day and the planning group for the workshop.

Several meetings were held to iterate the workshop concept and to share different tasks from advertising to the logistics during the workshop. It was acknowledged that in order to be able to follow the design of the workshop, participating students should preferably have prior knowledge in peace and conflict studies.

1.1 Advantages for co-creating workshop

Including student organizations in the planning process ensured that the core idea and the teaching methods were based on the needs and interests of the students. Inclusion of the students to the planning process created a feeling of ownership among the student organizations and helped the recruitment process of workshop participants. Cooperation also shared the burden of advertising, organizing the infrastructure of the workshop environment and overall implementation of the workshops.

For members of the student organizations the process gave practical experience on how to create study activities in an agile way, credibility to act as a partner with respected (state actors, academia, NGOs) stakeholders and an interesting academic possibility in the fields of crisis management and mediation that are currently underrepresented in Finnish higher education system.

2. Structure of the workshop

Hussein al-Taee, CMI

Hussein al-Taee, CMI

The workshop was divided into three different parts: the orientation phase, the participatory workshop and reflecting the learning experience. This structure was decided to be suitable concerning the limited amount of time available for the workshop. The three-step structure also ensured that students had the possibility to analyze the conflict step-by-step from different angles.

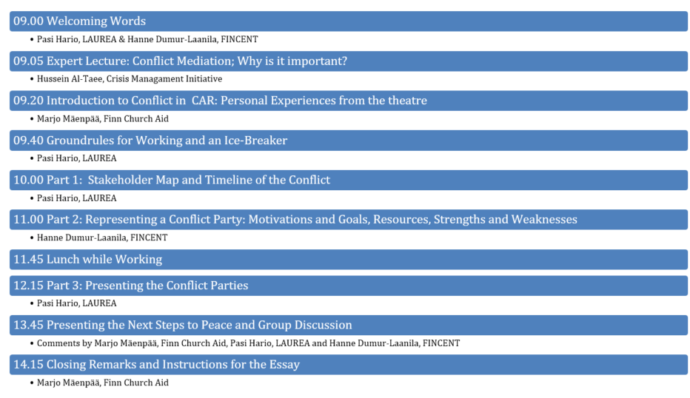

Table 1. Schedule of the workshop

Table 1. Schedule of the workshop

2.1 Orientation phase

Prior to the workshop, the participants were given a reading package and preliminary questions to ensure a baseline for their background knowledge. This also saved time as there was no need to go through the basics of the conflict before the workshop activities. During the workshop, students had the pre-material available, which ensured the rapid search of specific and detailed information whenever needed.

2.2 Participatory workshop

The planning group saw the importance of participatory approach during the workshop in order to achieve the learning objectives. During the entire workshop, participants were working in multi-disciplined, small teams of 5 to 6 peoples, which ensured that participants stayed concentrated and motivated.

Efforts were made to motivate and inspire the participants of crisis management and conflict prevention. For example, the opening speech inspired participants by offering practical tools for participants to use in the workshop. Students were also given house rules such as to respect themselves as experts and their workshop colleagues as equals. Lastly, the students were offered a glimpse of the humanitarian work and first-hand information of the country by one of the facilitators worked in the Central African Republic.

Multidisciplinary team of students participating the workshop

Multidisciplinary team of students participating the workshop

During the first phase, the groups were given tasks to build a timeline of the conflict and a stakeholder map. The idea of the first phase was to bring the participants to the same line in terms of conflict dynamics.

Throughout the second phase, each of the group worked with a given conflict party. The groups analyzed the motivations and goals, resources, strengths and weaknesses of their respected stakeholder. The parties represented by the groups consisted of key international organizations such as UN, EU, government of the “host country” and its key armed groups.

The third phase was dedicated to further analysis of the conflict situation and possible steps to peace. In the end, each group created their own roadmap to peace (comprehensive or negative peace).

3. Conclusions

3.1 Shortcomings

The timetable from November 2017 until May 2018 was too strict in order to attach the workshop as a part of National Defence University’s and Police University College’s students’ academic curricula. However, in the future, it would be beneficial to have participants also from the military and police educational institutions as EU, and other mission and operations nowadays consist of civilian, police and military personnel.

In order to include a simulated mediation between the respected conflict parties, the workshop should have lasted longer or some of the activities during the workshop should have been organized as preliminary tasking to save time.

Lastly, the given feedback questionnaire was not filled collectively after the workshop and caused only a few answers to be turned in. This was partially due to the tight timetable especially at the end of the workshop, which hampered the time spot. However, the few answers suggested that the expert lecture on CAR was overlapping with the pre-reading material and could have concentrated more on the expert’s personal experiences in the conflict zone.

3.2 Successes

Even though the workshop was a pilot, it was considered as being a success. Participants stated that there is still much more room for research based workshops for conflict analysis, where students could actually learn from the real conflicts and reflect their ideas and thoughts together with experts.

As the timetable to plan and organize the workshop was tight, it was crucial to build the initial planning team relying on existing reliable partnerships. FINCENT and Laurea have a successful track record of crisis management projects and it was natural to continue their fruitful cooperation in this project.

Involving the student organizations in the co-design process ensured that the teaching objectives, material and learning methods met the participant needs. It also helped the recruitment of the participants and shared the burden of organizing the logistics during the event.

The process involved students from multiple academic disciplines, some having even experience from crisis management duties. This ensured that the co-working in participatory workshop resulted as balanced and insightful views on conflicts.

While the questionnaire results suggested, that the expert lecture on the current situation in CAR could have been based more on personal experiences, the opening lecture on introduction to mediation was highly appreciated and motivated the participants of the tasking. It was beneficial to get a well-known expert to this role in order to bring the feeling of importance for the workshop.

Also, the verbal feedback suggested that the participants appreciated the dissemination of the IECEU research results and saw the workshop as a good way to supplement the limited higher education offering on crisis management and conflict studies.

References