The European education concept of Blended Intensive Programs (BIP) changes how both teachers and students see international education opportunities. A cross-institutional educator team plans and executes the course. Students from the participating universities learn to study in a non-native language with different teaching styles and in international teams. This article introduces BIP Masters’ implementations at Laurea University of Applied Sciences (Laurea). Moreover, we define BIPster (#BIPster) as a contemporary actor in this modern educational setting.

Short-term internationalisation online and in-exchange

The European Commission (2024a, 2024b) advances new flexible mobility formats for teachers and students that combine physical mobility with virtual learning as Blended Intensive Programmes (BIPs). Besides the official term, BIPs are sometimes referred to as “Blended International Projects”. Both names coin the essence of the context: transnational and interdisciplinary co-operation as a short-term internationalisation. A typical BIP entails online studies and at least one intensive week, where students get the chance to learn in challenge-based projects with local work life partners (see figure 1). Hence, BIP promotes access to international organisations during the intensive week challenge.

Figure 1. BIPsters visited KONE Corporation, Spring 2023. (Photo: Tarja Chydenius)

Figure 1. BIPsters visited KONE Corporation, Spring 2023. (Photo: Tarja Chydenius)

BIPs respond to students’ international education challenges

Statistics (Opetushallitus 2022) indicate decreasing student mobility and universities of applied sciences are still far from the peak years leading up to the pandemic. While mobility interest in total is falling, short mobility opportunities are popular.

BIPs offer internationalisation both abroad and at home. During a BIP, students and staff alike are immersed in new cultural practices in an intercultural context (Gögele and Kletzenbauer 2023). Thanks to its short-term and intensive characteristics, BIPs are more accessible for students. BIPs bring a chance toward inclusive international learning, in contrast to long exchange periods which are often a benefit for the financially privileged only (De Wit 2023).

At Laurea level, BIPs are offered as complementary studies at both Bachelor and Master level. This article focuses on Laurea BIP implementations for master’s students. They are often full-time employees, coming from diverse backgrounds and having different expectations of education (Tossavainen and Kaartti 2022; Tossavainen and Luojus 2019). Moreover, the life of adult students restrains them from longer exchange periods. BIPs can be achieved.

English has become a lingua franca practically on most international, professional contacts and fora. A clear “Englishisation” (Dannerer, Gaisch & Smit 2021) of higher education studies is observed in European countries. Yet, some Finnish master’s students are reluctant to participate in courses offered in English (at Laurea) as they underestimate their language proficiency. Thus, BIPs provide a comfortable platform to overcome such anxiety as both students and teachers are non-native English speakers. We believe that this experience generally encourages further internationalisation and working in larger ecosystems.

We define BIPster (#BIPster) as a participating actor in a BIP. The participant can be a student, a teacher, or other staff member. We also welcome the case challenge commissioners to join the BIPsters family.

BIPs are a response to the international needs of working life

Contemporary conditions require international cooperation. Organisations consider internationalisation, to access new markets, to tap into diverse customer bases or to attract job seekers. Thus, continuous development of language skills, intercultural competences and international relations is pivotal (e.g., Molinsky 2007). Today technology facilitates international cooperation and provides a gateway for cross-border activities. Fast-paced, intensive BIPs simulate real working where the first contacts and interactions are often initiated online. The online part brings BIPsters together and familiarises them collectively with the theme. The learning assignments are executed in multicultural and multidisciplinary student teams which already urge students to develop cultural awareness and skills (figure 2).

Figure 2. The French telecommunication company ORANGE invited BIPsters in Paris, Fall 2023. (Photo: Tarja Chydenius)

Figure 2. The French telecommunication company ORANGE invited BIPsters in Paris, Fall 2023. (Photo: Tarja Chydenius)

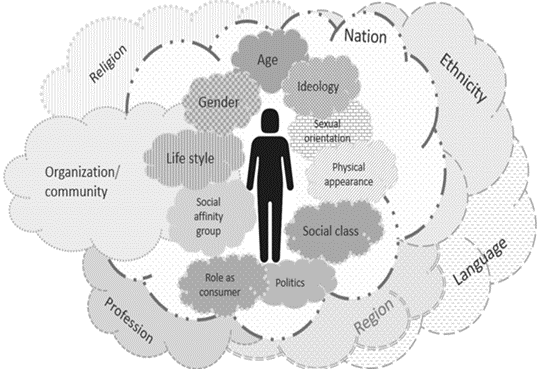

BIPsters are exposed to diverse cultural contexts (figure 3) at the same time, developing their self-awareness as “cultural hybrids” (Chydenius 2020). This constant cultural identity negotiation prepares for cross-cultural code switching needed in multicultural interactions. This refers to an ability to change one’s communication or behaviour for the purpose of mutual understanding or a desired adaptation into an unfamiliar cultural context (Barrett 2012; Molinsky 2007).

Figure 3. Individuals are embedded within cultures simultaneously (Chydenius 2020)

Figure 3. Individuals are embedded within cultures simultaneously (Chydenius 2020)

Molinsky (2007, 633) concludes that cultural adaptation is critical in international work environments. The multicultural and interdisciplinary BIP offer a such platform for learn to function appropriately.

Teacher facilitates physical mobility

Higher Education Institutions remain feeble if they are unprepared to seize opportunities. An overall framework, operational model with defined roles and activities would support the teacher considering a BIP. The Pioneer Alliance consists of ten European Universities and provides a network for teachers to collaborate. BIPs, however, require efforts to unify the main dimensions identified by Tossavainen (2009) as pedagogy, operative arrangements, decision-making, and finance.

First, the BIP partners agree upon the pedagogical choices and collaboratively develop the BIP. During the online part, the responsibilities are divided by the teachers’ professional competence. Learning management system and schedules are smoothly agreed upon. However, the intensive mobility part remains to be organised by the receiving HEI. Thus, the BIP teacher becomes involuntarily a facilitator, organiser, and event manager. Operationalising the intensive week is not the teacher’s professional field. From experience so far, international services, who are responsible for the agreements between the partners, mobility arrangements, housing arrangements and extracurricular activities, provide support. Nevertheless, the bulk of the workload remains on the teacher. The responsibilities vary from planning a detailed schedule, booking the learning facilities, ordering food and refreshments, inviting internal and external speakers, to negotiation with commissioners for the case challenge. Additionally, s/he is left to organise specific meetings for visiting and local staff, and oversees the overall activities. The teacher also communicates the programme, arranges materials and guidance, sends the invitations, ensures visibility internally and externally. Teachers are capable of mutually beneficial decision-making. It is noteworthy though that a BIP is a joint experience for all participating HEIs. The financial support for mobility comes from the Erasmus + programme. Other financial commitment is required as a work time investment of a teacher. We suggest this to be annually at least 150 hours at receiving HEI and otherwise 100 hours.

Our experience with BIPs is in line with Gögele and Kletzenbauer (2023), who emphasised the participants’ excitement of running BIPs in the first run. The initial enthusiasm reversed the motivation as the realisation of the extensive workload materialised. To avoid demotivation, and to support and systematise the future BIPs, we decided to draft a guidebook to smoothen colleagues’ participation in a BIP.

BIPs successfully implemented at Laurea

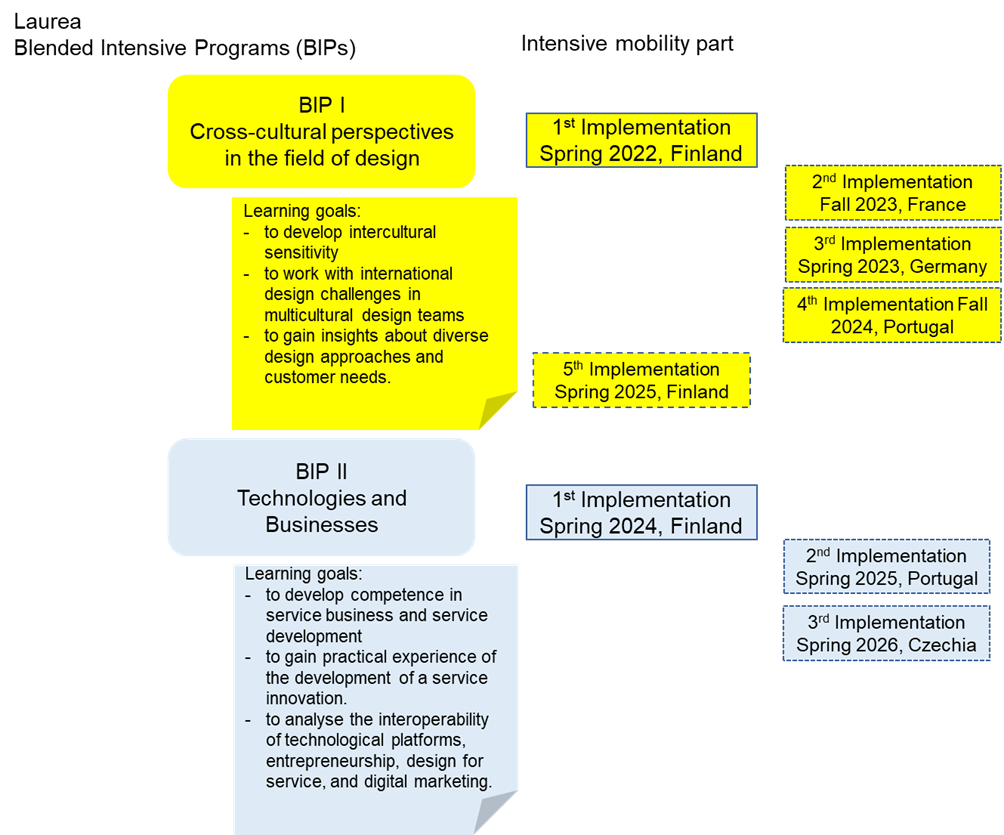

Laurea has so far implemented two differently themed BIPs (figure 4). The “BIP I” is named “Cross-cultural perspectives” and it flexibly follows a culture-sensitive design theme. The “BIP II” is named “Technologies & Businesses” and it aggregates technological issues with the dynamic service business.

Figure 4. Current Blended Intensive Programs at Laurea University of Applied Sciences (Tossavainen 2024)

Figure 4. Current Blended Intensive Programs at Laurea University of Applied Sciences (Tossavainen 2024)

The “Cross-cultural BIP” was piloted at Laurea in June 2022. The learning goals are to develop intercultural sensitivity and to work with international design challenges in multicultural design teams, and to gain insights about diverse design approaches and customer needs. The partner HEIs are Gustave Eiffel University, France, University from Portugal, and Cologne International School of Design (KISD) Germany, and Laurea. BIP I’s are organised bi-annually, and the student participation is limited.

BIP II ‘Technologies & Businesses’ focuses on the interconnections of technological issues with the dynamic service business landscape (figure 5). It started in the spring 2024. Each annual implementation has a distinct flavour. The participating HEIs are Gustave Eiffel University, Iscte University, and Tomas Bata University, the Czech Republic. BIP II’s are organised annually.

Figure 5. BIP II Technologies & Businesses marketing material (Lukas Koutny 2023)

Figure 5. BIP II Technologies & Businesses marketing material (Lukas Koutny 2023)

BIPs have proved to be an agile way of integrating international and intercultural dimensions into education. So far, BIPsters have enjoyed the internationalisation opportunities. Although there is always room for improvement, the student experiences have been overwhelmingly positive. The staff members, too, have found BIPs enriching and widened their professional perspectives. We can strongly recommend students, teachers, and staff to become “BIPsters.”

For information about the BIPs at Laurea, please view the video (in Finnish, by Juha Takanen, 2024).

About the authors

Tarja Chydenius, Lecturer, PhD, Associate in Laws

Tarja has several years’ teaching and research experience in the fields of service and legal design, intercultural communication and cultural competences. Her PhD dissertation focused on culture’s role in designing for services.

Päivi J. Tossavainen, Principal lecturer, D.Sc. (Econ), AmO

Her Master’s Degree and the Doctorate Degree are in International Business. Prior to the Laurea position, she worked in global development operations in a multinational firm. At Laurea, she continues to promote internationalization and collaboration.

References

- Barrett, M. 2012. Intercultural competence. European Wergeland CentreStatement Series, 2 (23-27). Oslo, Norway: European Wergeland Centre.

- Chydenius, T. 2020. Culture in Service Design. How service designers, professional literature and service users view the role of national, regional and ethnic cultures in services. JYU Dissertations 199. University of Jyväskylä. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences.

- European Commission 2024a. Blended Intensive Programmes in KA131 Higher Education projects. European Commission. Accessed on 21.2.2024.

- European Commission 2024b. Blended Intensive Programmes. Blended Intensive Programmes – Erasmus+ & European Solidarity Corps guides – EC Public Wiki (europa.eu). Accessed on 21 February 2024

- Dannerer, M., Gaisch, M., & Smit, U. 2021. 13 Englishization ‘under the radar’. The Englishization of Higher Education in Europe, 281.

- Gögele, S. & Kletzenbauer, P. 2023. Blended intensive programmes: promoting internationalization in higher education. Education and New Developments. 381- 383

- Laurea 2023. Strategy 2030. Strategy 2030 – Laurea University of Applied Sciences. Accessed on 21 February 2024

- Molinsky, A. 2007. Cross-cultural code-switching: the psychological challenges of adapting behavior in foreign cultural interactions. Academy of Management Review, 32 (2): 622–640.

- Opetushallitus 2022. Korkeakoulujen opiskelijaliikkuvuus on elpynyt koronan jäljiltä – yhä useampi vaihtoon lähtijä opiskelee ammattikorkeakoulussa. Tiedote 3.11.2022. Accessed on 28.2.2024.

- Tossavainen, P. 2009. Institutionalising internationalisation strategies in engineering education. European Journal of Engineering Education.

- Tossavainen, P.J. & Kaartti, V. 2022. Tiedon merkitys – uhkapeli, palapeli vai älypeli? AMK –lehti/ UAS Journal. 2/2022.

- Tossavainen, P.J. & Luojus, S. 2019. Incorporating Service Design Into Education Of Future Managers. EURAM 2019, EURAM Conference proceedings, Lisbon, Portugal. European Academy of Management. ISBN 978-2-9602195-1-7.

- De Wit, H. 2023. Internationalization in and of Higher Education: Critical Reflections on its Conceptual Evolution. Chapter 2 in Engwall, Lars and Börjesson, Mikael (Eds.). Internationalization of Higher Educations Institutions. Cham: Springer.