This article presents circular textile solutions which were developed in the prototyping process in the Baltic2Hand project (2023-2026). Baltic2hand project supports companies in developing circular business models and solutions to increase second hand sales or decrease textile waste.

Picture by Pikisuperstar / Freepik

Picture by Pikisuperstar / Freepik

The Baltic2Hand project aimed at creating solutions that would be viable circular business models for the textile industry. Prototyping tools for creating circular prototypes and helping industries to turn towards circularity are still rare (Maselkowski & Romero 2024; Geissdoerfer et al. 2018; Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2022). Therefore, we want to demonstrate the process of developing circular textile solutions with service design prototyping tools and show some of the resulting solutions. Microsoft Co-pilot has been used to improve the clarity and grammar of this article.

How the circular textile prototypes were developed

Prototyping is the process in which designers convert an idea into a physical or tangible representation with varying levels of detail and accuracy and then test it with actual users (Brown & Katz 2009). In d esign and innovation processes, it is common to ideate first a large number of possible solutions, then decide which ones are most feasible for implementation. The chosen ideas are often prototyped before actual implementation. Some common methods for prototyping include concretizing the solutions by making a model of Legos, cardboard or other cheap materials, interactive prototypes created with digital tools, or simulating the service with play-acting. (Blomkvist & Holmlid 2011; Holmlid & Evenson 2007; Stickdorn & Schneider 2011).

Altogether 11 companies took part in the prototyping of the Baltic2Hand project. Four companies were from Finland, five from Sweden and one from Estonia. One of the companies operates both in Finland and in Estonia. All the companies were eager to promote and increase the reuse of second hand textiles and/or reduce textile waste in their business. The ideas which the companies wanted to develop were, for example, a shop-in-shop model for a fashion brand to sell its own second-hand clothes, a sustainable fashion show and a marketing campaign for leather care and restoration services.

The prototypes in the Baltic2Hand project were developed through a series of four workshops, where companies received support to understand the concept of prototyping, its benefits, and the various tools and methods available. Each company was guided individually in creating and testing their prototype with users. After completing the prototyping phase, the companies began planning pilot projects, which represent the final stage of experimentation before full implementation of the solution (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2011).

The workshops followed a clear progression. In the first workshop, companies focused on refining their initial ideas. The second workshop involved selecting appropriate prototyping methods and creating a testing plan to be carried out between the second and third sessions. During the third workshop, companies presented the results of their user testing and made decisions about necessary changes to their prototypes. The fourth and final workshop was dedicated to presenting the completed prototypes and initiating pilot planning.

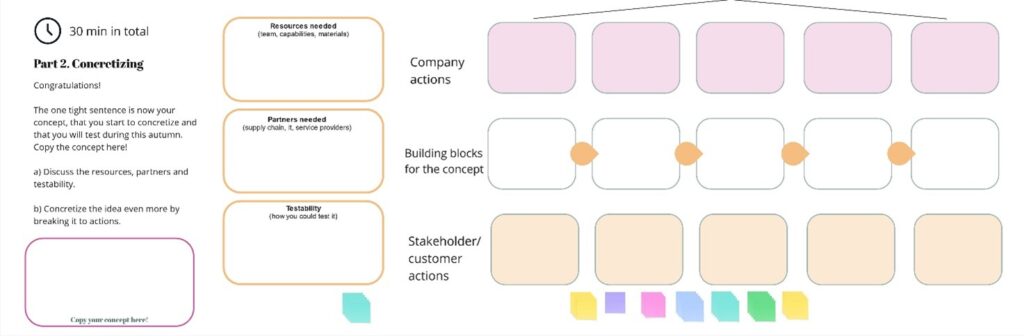

Baltic2Hand provided a selection of prototyping tools and methods, allowing companies to choose those that best suited their needs. Baltic2Hand project guided the prototyping process with a structured Miro board, outlining each step and facilitating collaboration between the companies and the Baltic2Hand support team. The board included descriptions of prototyping tools, templated to clarify the concept (example in picture 1), resources for defining the value proposition, and a template for a testing plan. These tools helped companies refine their ideas, determine effective ways to test their prototypes with real users, develop business models, and explore how to create circular textile solutions.

Picture 1. Example of a prototyping tool in Miro: Concretizing the idea (Mäkiö 2024).

Picture 1. Example of a prototyping tool in Miro: Concretizing the idea (Mäkiö 2024).

Additionally, the project supported companies in conducting user testing and assisted in recruiting participants. This phase was crucial for identifying potential weaknesses and challenges before moving on to piloting. Some of the issues uncovered during testing included the need for a strong ecosystem to support circular solutions, the importance of scalability in the face of uncertain funding, and the lack of data on the volume of returned clothing. One company also discovered that using authentic images in communication campaigns was essential for connecting with their target audience. By recognizing these challenges early, companies were better prepared to approach piloting with realistic expectations.

Next, we introduce four circular textile prototypes developed through the Baltic2Hand project.

Circular textile solutions developed in Baltic2Hand project

Shop-in-shop model for second hand clothes

The idea of the prototype was to create a shop-in-shop model for a Finnish fashion brand. The idea was that the brand could sell its own brand second hand clothes in their brick-and-mortar store, thus making the return of clothes to the store easy and convenient . The aim was to keep clothes in circulation, increase the use of second and clothes as well as to reduce textile waste.

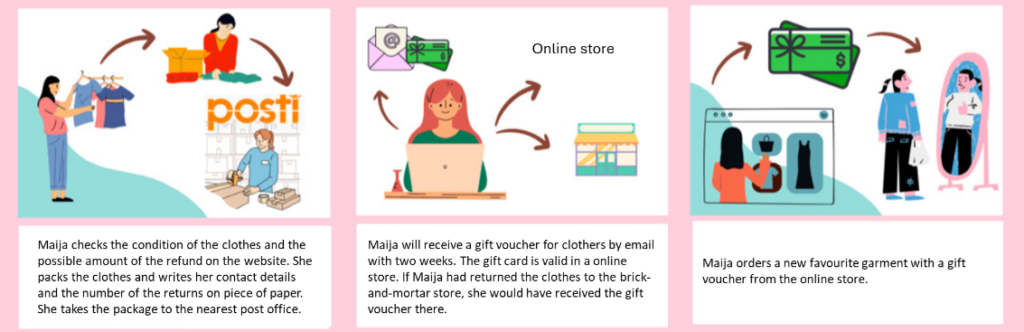

The prototyping team created a storyboard (picture 2) which described the customer journey for returning clothes back to the store by post or in person. The storyboard also included options on how the customer would get paid for the returned items. The prototype was tested by sending a survey to customers who follow the brand’s social media channels or subscribe to their newsletter. Additionally, five customers were interviewed to gain a deeper understanding of how they felt about the shop-in-shop idea for second hand clothes as well as the return process. The feedback was very positive and it helped to clarify the most important actions in the process. Some suggestions were also provided, including the possibility of adding or supporting rental services, collaborating with other brands or shops, or selling second hand clothes online. These ideas can be explored further.

The biggest challenge in the prototype was to clarify the more detailed actions the company needs to take, such as creating an online return form and working out how the credit will be paid for clothes returned in-store versus by post. Predicting the volume of returned clothes at the start of the pilot will be difficult. However, the convenient process to sell the brand’s second hand clothes in the store will encourage customers to recycle their clothes more frequently and will further improve the brand’s image as a responsible operator in the Finnish clothing industry.

Picture 2. An example of the storyboard created for the pilot (Nikola 2025).

Picture 2. An example of the storyboard created for the pilot (Nikola 2025).

Slow fashion show prototype

Slow Fashion show was one of the prototypes in the Baltic2Hand project. This is an outdoor fashion show concept which aims to unite 20 second hand stores in Södermalm, Stockholm, and showcase the diversity and sustainability of second hand clothing.

To test this prototype, a storyboard with the concept was developed and shared via an online survey. The survey was shared on social media groups focused on activities in Stockholm. The survey aimed to gauge general interest, user needs, and feedback for the feature s in the fashion show. The prototype received positive feedback, with requests to incorporate fashion activism and performance elements while keeping the focus on the show itself. Traditional educational features, such as workshops and speeches, were deemed less desirable unless creatively integrated into the show.

Challenges included estimating the scale of the show amidst uncertain funding. The show concept was designed to be modular and adaptable, allowing for scalability based on external circumstances.

The survey confirmed an interest in this type of activity. It also helped to narrow down the features in the show. Showcasing circular fashion in a playful and open format helps to increase its visibility to less sustainability-focused consumers. It also creates more awareness around the sustainability of consumption choices. Finally, it helps deconstruct the exclusivity of conventional fashion shows, by making the experience accessible and educational to different demographics.

Second hand clothing into school projects

The aim of the prototype of an Estonian company was to introduce the idea of integrating second hand clothing into fashion projects within schools and educational settings while promoting sustainable fashion choices. Additionally, the project aimed to equip students with new skills for working with recycled materials.

To be able to promote and test the idea in schools and with handcrafters and second hand shops in Estonia and Finland, the company developed a prototype slide deck titled ”Upcycled Fashion is the Future for Everyone!” The deck introduced the concept of integrating second hand clothing into school fashion projects and equipping students with skills to work with recycled materials

The company conducted six interviews in order to gather feedback on the prototype slide deck and the concept. Feedback was largely positive, though usability testing revealed areas for improvement, prompting adjustments to enhance clarity and address partner expectations.

The prototype highlighted both opportunities and challenges. While the idea was well-received, securing long-term commitments from partners may require additional incentives or resources. Overall, the prototype strengthened the project’s foundation, offering benefits not only to the company but also to the broader circular fashion ecosystem by fostering sustainability and education.

Marketing campaign for second hand leather items

One of the prototypes in Baltic2Hand project was completed with a company providing services for leather care and restoration. The prototype included a fake ad and survey which aimed to gather insights from social media viewers. The fake ad featured a pair of red leather shoes with a catchy slogan to capture attention (picture 3). The survey asked targeted questions to uncover what types of content would engage the audience, where they typically search for information, and if they are willing to pay for leather care and restoration services.

Survey results provided valuable insights into content that resonates with the target audience, such as authentic images, the story behind the business, leather product care tips, and transformation videos. Based on this feedback, a social media plan was developed, outlining post topics, suggested hashtags, and images provided by the company.

Challenges included scaling personalized content creation, which could be resource-intensive. The prototype helped improve brand communication and engagement, aligning content with audience values and preferences.

Picture 3. The fake ad (Howlader 2025).

Picture 3. The fake ad (Howlader 2025).

Conclusion

The Baltic2Hand project successfully demonstrated how prototyping can be a powerful method for developing viable circular business models in the textile industry. The project provided a structured process with tools tailored to each phase of prototyping, while also offering personalized support to participating companies. This combination enabled businesses to design solutions that aligned with their unique needs. The experience suggests that successful prototyping requires both clear guidance and flexibility to accommodate individual approaches.

All in all, the prototyping process helped companies clarify their needs, test ideas, and gather valuable feedback. It also fostered collaboration and knowledge-sharing among participants. However, time constraints and limited resources were identified as challenges, suggesting that future iterations of the project could benefit from extended timelines and additional support. Personalized support from the design team played a significant role in helping companies develop solutions tailored to their specific business contexts.

Importantly, several companies expressed a strong interest in continuing to develop their prototypes, with some already planning real-world implementation. This indicates that the project not only generated innovative concepts but also laid the foundation for lasting impact. By encouraging experimentation and collaboration, Baltic2Hand has empowered companies to take meaningful steps toward more sustainable business models, contributing to a broader transformation in the fashion industry toward circularity and environmental responsibility.

Baltic Second-Hand – As good as new: Enhancing the behavioral and business change of the second-hand textile industry in the Central Baltic region

Baltic2Hand project improves textile reuse and reduces textile waste in the second-hand market from 1.4.2023- 30.3.2026.

In the Baltic Second-Hand project, organizations in the fashion and textile industry in Estonia, Finland, Latvia, and Sweden develop their business models towards sustainability and circular economy. Using a service design process, the project maps and designs new opportunities in re-using textiles and in reducing textile waste. The project tests and pilots potential solutions and promotes consumer use of secondhand textiles.

Baltic2Hand is funded by an Interreg Central Baltic Programme 2021-2027 project that is co-funded by the European Union.

References

- Blomkvist, J. & Holmlid, S. 2011. Existing prototyping perspectives: considerations for service design. Nordes, (4).

- Brown, T. & Katz, B. 2009. Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Geissdoerfer, M., Morioka, S., De Carvalho, M. & Evans, S. 2018. Business models and supply chains for the circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 190, 712-721. Article from Apollo. Accessed 27 March 2024.

- Holmlid, S., & Evenson, S. 2007. Prototyping and enacting services: Lessons learned from human-centered methods. Proceedings from the 10th Quality in Services conference, QUIS (Vol. 10).

- Lüdeke-Freund, F., Breuer, H. & Massa, L. 2022. Sustainable Business Model Design: 45 Patterns. Frankfurt am Main: Druck- und Verlagshaus Zarbock GmbH & Co. KG.

- Maselkowski, S. & Romero Montoya, J. 2024. Driving circularity in textile and fashion businesses during prototyping. Laurea University of Applied Sciences. Master’s thesis.

- Stickdorn, M., & Schneider, J. (eds.). 2011. This is service design thinking: Basic, tools, cases. Bis Publishers.

Pictures

- Picture 1. Example of a prototyping tool in Miro: Concretizing the idea by Inka Mäkiö (Turku University of Applied Sciences). 2024. The picture was created in Baltic2Hand project.

- Picture 2. An example of the storyboard created for the pilot by Tanja Nikola. 2025. The picture was created in BalticHand project.

- Picture 3. The fake ad by Elena Howlader. 2025. The picture was created in Baltic2Hand project.

In this article, Microsoft Co-pilot has been used in formatting the text to improve clarity and grammar.