In this article we explore the practical facilitation of flow in foreign language learning, building upon theoretical concepts and previous research. We highlight the role of practitioners, emphasizing that teachers are facilitators shaping language learning experiences. We discuss the relationship between flow, enjoyment, and task-challenge alignment. We also outline practical strategies to foster flow, such as task design and interactivity. Moreover, we share insights from an expert teacher of Finnish as a foreign language. Our article underscores the importance of maintaining a balance between challenge and autonomy to sustain flow. Additionally, it showcases a collaborative video project as an effective practice. Ultimately, this paper contributes to the study of flow in language learning and its application in Finnish language education within the MALL project.

Photo by Clarissa Watson on Unsplash

Photo by Clarissa Watson on Unsplash

Introduction

This article complements our previous work on flow in foreign language learning (Leminen, Rivera-Macias, Lydén & Heikinmatti 2023) by focusing on practical methods to facilitate flow within the context of the Multisensory approaches to language learning (MALL/in Finnish: Moniaistinen kosketus uuteen kieleen, MAKU) project. This project is dedicated to investigating and enhancing the acquisition of the Finnish language among immigrants in workplace settings.

In the MALL project, we recognize the vital role that practitioners play in language learning. Teachers are more than educators, in fact, they are facilitators who shape immigrants’ language learning experiences. To emphasize this, we have involved Finnish language organizations and teachers from the outset of the MALL project.

In this article, our primary aim is to explore the practical aspects of fostering the flow state during language learning. First, we will briefly introduce the concept of flow and its relevance to language learning. Then, we will share insights from an expert teacher of Finnish as a second language who is actively involved in the MALL project.

The Relationship Between Flow and Language Learning

Flow, as a concept, has been studied in connection with language learning since the early 1990s (Albert 2021; Egbert 2003). It is closely linked to the enjoyment of a task and the ability to maintain focused attention, enabling learners to advance their skills. Enjoyment in foreign language learning is often the result of aligning the challenge of tasks with the learner’s perceived ability (Dewaele & MacIntyre 2016).

Creating tasks that encourage positive self-efficacy beliefs and fostering interactions among learners with different language proficiency levels can promote flow (Aubrey 2016; Piniel & Albert 2017). Additionally, using dialogic, oral tasks with a cultural information exchange component can enhance the flow state (Aubrey 2016). Teachers’ personal experiences of flow and reflective practices also play a significant role in shaping students’ flow experiences (Tardy & Snyder 2004).

Flow and Anti-Flow in Language Learning

Flow experiences can be accompanied by anti-flow (Albert 2021). Anti-flow can manifest as apathy or anxiety, affecting learners’ emotions and experiences. The flow state tends to increase with learners’ progress. Group learning environments often promote flow, especially when they are all sharing the same physical space, whereas distractions in online learning settings, such as internet issues, can disrupt flow within group learning. (Dewaele & MacIntyre 2022; Dewaele, Albakistani, & Ahmed 2022.)

To promote flow in language classrooms, teachers are encouraged to maximize interactivity and include decision-making components in tasks. Allowing students to select task topics and prepare content can enhance their sense of control and investment in the task, fostering flow (Aubrey 2016). Gamification can also be applied to maintain students’ engagement (Kemppainen & Juntunen 2019).

Flow in Teaching Practice – Insights from an Expert Teacher

From the perspective of an expert teacher of Finnish as a foreign language, flow in language learning is often achieved through functional learning activities, such as projects, group work, arts, and crafts. Balancing the development of communication skills, such as listening, reading, speaking, and writing, is essential. Holistic approaches that combine these skills with interaction and mediation can facilitate flow more effectively than traditional exercises (e.g., fill-in-the-blank or read-and-answer tasks).

Online and offline learning environments both offer opportunities for flow experiences.

Online learning provides advantages such as focused concentration and flexible pacing, whereas offline learning offers multisensory experiences and nonverbal communication cues. Teachers should leverage the benefits of both environments (Ahola & Baliasina 2021).

Facilitating Flow in Language Learning

To promote flow, teachers can set creative or cognitive goals and parameters for tasks. These goals should allow for autonomy and empowerment, preventing learners from fearing they make mistakes even when diverging from the assignment. Regular feedback and assessment help maintaining motivation and the flow cycle. Teachers should also encourage students to define the difficulty level by offering loose task parameters, enabling learners to create their own rules, parameters, and challenges (Hall 2020).

A Collaborative Video Project as an Example

We wanted to explore language use situations at the workplace through codesign, by which we mean engaging in client-centric design processes aimed towards solving problems and challenges together, emphasizing collaboration and partnership (Moll et al. 2020). These language use situations were then turned into short videos that could be used in language learning. Figure 1, below, shows a situation where language learners were engaged in the cocreation of the personas (in terms of service design) that became characters in the videos.

Figure 1. Multisensory setting for codesign that leads to flow and language learning. Lydén (2023)

Figure 1. Multisensory setting for codesign that leads to flow and language learning. Lydén (2023)

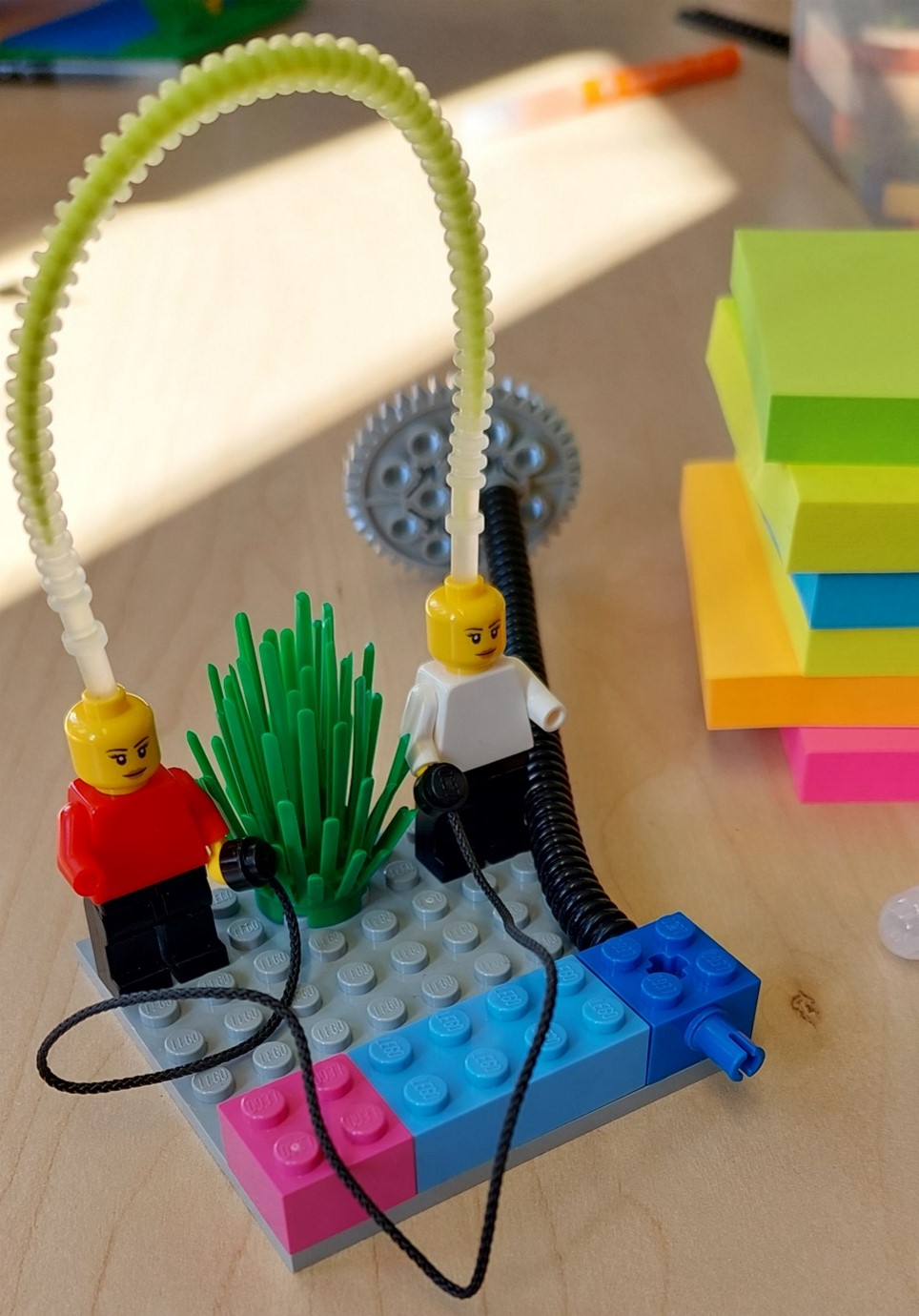

We had as our codesign partners a group of unemployed immigrants, who are currently studying Finnish and a group of Laurea students of social sciences. We used a serious play method, by which we mean the integration of playful elements into traditionally serious domains like work and organizational practices, challenging the boundaries between leisure and professional spheres, and exploring the potential benefits of incorporating playfulness into the workplace. More specifically, we used the LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® method, where the building bricks are used to collaboratively explore various topics or models. An example of a language use situation depicted through the LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® method is depicted in Figure 2, below, where language learners were encouraged to describe the meaning of their buildings and figures.

The tasks of preparing for the filming of the videos engaged the learners and students in various roles, such as scriptwriting, editing, makeup, and set design, all conducted in Finnish. As a side finding we experienced that the codesign processes and producing the videos were, in fact, an effective way to achieve flow in language learning. The participants wanted to interact with each other, and this meant they, according to their teacher who was also a participant in the process, used language much more than they would in a normal class setting. In retrospect we see how creating tasks that students can fulfill, ensured success, and promoted flow (Kemppainen & Juntunen 2019).

Figure 2. Language use situation as a conceptual LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® model. (Rivera-Macias 2023).

Figure 2. Language use situation as a conceptual LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® model. (Rivera-Macias 2023).

Closing Remarks

In conclusion, the pursuit of the flow state in language learning is far from arbitrary; it is a deliberate and thorough endeavour on the part of teachers. By affording learners the autonomy to set their own parameters, granting sufficient preparation time, and nurturing positive emotions, we pave the way for the flow state. As a final note, we emphasize that flow is not an abstract concept but an achievable objective through deliberate actions in the language classroom.

This publication is part of the ESF+ funded MALL project, coordinated by Laurea University of Applied Sciences, aimed towards promoting the rapid employment of immigrants in fields facing workforce shortages (MAKU-Hanke – Laurea-Ammattikorkeakoulu, n.d.). The project involves Haaga-Helia, Arffman Ltd., and Lingsoft Ltd. (MAKU-Hanke – Laurea-Ammattikorkeakoulu, n.d.). We would like to acknowledge the assistance of ChatGPT (3,5), an AI language model developed by OpenAI, for providing valuable editing and content refinement for this article.

Authors:

- Alina Leminen (PhD, Docent) is a cognitive scientist, who works in Laurea as Chief RDI officer. She has conducted research on, e.g., language learning, multilingualism, and the language development of immigrants. She is the Research Director in the MALL project.

- Hilkka Lydén (MScN, RN) works at Laurea University of Applied Sciences, C-unit, as an RDI Specialist and Project Manager. She has previously worked, for example, as a refugee counsellor in immigration services and as a nurse at a reception centre. She is a doctoral researcher at the Faculty of Art and Design at the University of Lapland, investigating the support of integration through design. In the MALL project, she is the Principal Investigator and project manager.

- Berenice Rivera-Macias (PhD) is a sociologist and psychologist working at Laurea as Project Specialist (MALL project). She has done research, for instance, on topics related to learning and teaching in higher education, and meso- and micro-level experiences of staff at public institutions.

- Samu Heikinmatti (MA in Finnish language) is an integration coach and Finnish teacher. He has been teaching Finnish for foreigners for 14 years of which 8 years online. He is specialized in e-learning, drama and gamification. Currently he is working in Arffman Finland as a coach and Project Worker in the MALL project.

References:

- Ahola, M. & Baliasina, M. 2021. Tekoäly – peikko vai pelastus? Tempus.

- Albert, Á. 2021. Flow in language learning: Issues of measurement. In G. Tankó & K. Csizér (Eds.), DEAL 2021: Current Explorations in English Applied Linguistics (pp. 35–64). Department of English Applied Linguistics, School of English and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University.

- Aubrey, S. 2016. Inter-cultural contact and flow in a task-based Japanese EFL classroom. Language Teaching Research, 21(6), 717–734.

- Dewaele, J. M., Albakistani, A., & Ahmed, I. K. 2022. Is Flow Possible in the Emergency Remote Teaching Foreign Language Classroom? Education Sciences, 12(7).

- Dewaele, J.-M., & MacIntyre, P. 2022. “You can’t start a fire without a spark”. Enjoyment, anxiety, and the emergence of flow in foreign language classrooms. Journal Applied Linguistics Review 16.6.2022.

- Egbert, J. 2003. A study of flow theory in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 87(4), 499–518.

- Hall, W. 2020. What is Assessment as Learning? Enhancing teaching with data. Century.

- Kemppainen, J., & Juntunen, J. 2019. Pelisuunnittelijan peruskirja. Aviador.

- Leminen, A., Rivera-Macias, B., Lydén, H. & Heikinmatti, S. 2023. Flow in Foreign Language Learning. Laurea Journal 14.11.2023.

- Moll, S., Wyndham-West, M., Mulvale, G., Park, S., Buettgen, A., Phoenix, M. Fleisig, R. & Bruce, E. 2020. Are You Really Doing ‘codesign’? Critical Reflections When Working with Vulnerable Populations. BMJ Open 10, no. 11/2020: e038339.

- Piniel, K., & Albert, Á. 2017. L2 motivation and self-efficacy’s link to language learners’ flow and anti-flow experiences in the classroom. In S. L. Krevelj & R. Geld (Eds.), UZRT 2016 empirical studies in applied linguistics (pp. 90–103). FF Press.

- Tardy, C. M., & Snyder, B. 2004. ‘That’s why I do it’: flow and EFL teachers’ practices. ELT Journal, 58(2), 118–128.