In the future, digital health and social care services will become fast-growing worldwide businesses (European Commission 2012). Successful customer-orientated services require co-creation by multiprofessional teams (Björk & Ottosson 2016). Therefore, the main objective of the Multiprofessional Digital Developers’ Intensive Course (Muddie 3) was to offer Nordic-Baltic experts and students the possibility to share good practices and to work together on customer-oriented service designs in digital health and welfare. In practice, the intensive course formed a platform for workshops where the participants designed and built up pilot services for eHealth and eSocial care. In the Developer of Digital Health and Welfare (DeDiWe) Services project 2015–2018, funded by the Central Baltic Programme, a new multiprofessional 30-credit-point curriculum was developed, with a focus on learning in multiprofessional groups in an international context.

The Muddie Intensive Week in Riga, Latvia, during spring 2019, offered great experiences for teachers and candidate students working together in multiprofessional teams developing eHealth and welfare services. In our case, multiprofessional teams were formed with students who were studying health care, business, IT or design. The multiprofessional environment enabled people from various disciplines with specific domain knowledge to collaborate and share expertise. Seven partners from higher education organizations took part in this intensive week. Four participants were Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS) in Finland, one was from Estonia and two were from Latvia. This Service Design Model for Higher Education in the Context of Digital Health and Wellbeing is aimed to provide tools and methods for multiprofessional groups of teachers who guide students in developing customer-centric digital services for health and social care (Ahonen et al. 2018). The aim of this article is to describe the service design intensive week model and to help the reader apply this model in future learning contexts.

eHealth and Welfare Services in Europe

Health and social care are in the middle of a paradigm change as citizens are becoming more and more aware of their health and of the possibilities for them to monitor it. Citizens can use analytical tools to understand their health and wellbeing and thus take a more proactive stance in disease prevention. They are keen to collect data on their health and to see the results of the data analysis, and they are eager to use the information to change their health behaviour.

Currently, health-care service delivery processes suffer from inefficiencies and a lack of health-care workers (WHO 2018; European Commission 2013). There are many cases of how technology can be used in the provision of health and welfare services, such as telemedicine solutions, which enable remote treatment of patients (Sabesan et al. 2012). Other examples are data analytical tools, which increase the effectiveness of making clinical decisions (Jiang et al. 2017) and wearable technology, which enables patients to manage their chronic diseases more effectively (Gordon 2018).

Remote treatment and self-measuring of different paradigms offer solutions for situations where there are great distances between patients and hospitals. Data can be stored in a secure cloud, from which nurses or doctors can access and analyse it and give patients new orders regarding self-treatment. Digital health and welfare services could also help to tackle the growing need for health-care services caused by the aging of the population. Smartphones, new 5G technology and AI open up possibilities for providing better care for elderly people without their needing to move away from home. 5G also increases possibilities for better diagnosis, such as real-time, long-distance heart monitoring in hospitals using data sent from patients’ homes. 5G would also enable the transferring of X-ray images.

The main aim of digital health and welfare services is to tackle the challenges faced by health-care systems. Regardless of the increase in research and clinical evidence regarding different eHealth solutions, many barriers for their implementation in clinical processes remain (Granja et al. 2018). One of these barriers is the insufficient digital skills of the health-care workforce, a problem that has led to the need for the development of new educational programmes (Gaskell 2018). However, eHealth services should be as user friendly as possible and lead to the usage of service design methodology concepts in the health setting (Teso et al. 2013).

Technology

As personal use of technology among young adults is widespread and growing, it is paramount that the health-care sector also works to embrace the changes and the new technology in a safe and productive way. If given the right guidance, students of today have the opportunity to lead the development of digital services in health care using modern technology. New EU legislation guides the development and the use of technology for medical purposes (EU Regulation 2017/745; Regulation EU 2017/746), while wellbeing services are primarily guided by EU Regulation 2016/679. Students must critically examine technology and be able to distinguish hype from substance. Strickland (2019) provides practical examples of how technological hype without substance are presented to students in order to provide them with an understanding of how to identify such situations.

Developing critical thinking in technology management is based on structured and guided learning that helps students to fathome the opportunities and pitfalls while contributing to new thinking. Students are exposed to technology through trends that possess the ability to both transform and disrupt health care. Current trends that are highlighted include IoT/mobility in the form of sensors with the ability to digitize physical spaces and then communicate the measurements through the Internet. Intelligent services are introduced through examples and explaining how data is stored and processed, which are then used for training models and for verifying their accuracy (Pulkkis et al. 2017). New types of human-computer user interfaces are explained, and students get to see how virtual reality and augmented reality can be employed in different use cases. The technology aspect also includes a discussion about which technologies have worked or failed while also explaining why the largest challenge is often not a technology issue, but one of agreeing on requirements and the alignment of goals.

Design Thinking behind the Service Design

Design cannot solve all problems, but it can be a part of every solution (WDO 2017). Design thinking is the philosophical background of a service design methodology. The design thinking process needs to start with the will to understand the customers’ lives from an expanded point of view (i.e. not just the one need, but all the needs around it). The design thinking process has three phases: 1) inspiration, which starts from designers believing in success, understanding the problem from all perspectives and determining what has changed or will be changed around the topic; 2) ideation, which encourages designers to find all different kind of ideas and sketches about the topic from different points of view, build creative frameworks, apply interactive thinking, use customers’ mindsets, prototype and test, tell more stories and communicate with different parts, and prototype some more tests with users; 3) implementation, which entails designers executing the vision, helping to market design a communication strategy, making the case to the business and spreading it to the world (Brown 2008).

Teachers’ Roles

Teachers can form a group that is multiprofessional and multicultural. However, although teachers come from different disciplines, it is essential that there is a background in service design culture, service design processes and design thinking (Tschimmel 2012). In addition, teachers from the health and social care sectors and others with an information technology (IT) background—either IT engineers or IT business administrators—are also needed. It is also crucial to have at least one teacher from each school so that the students have a contact teacher at each school.

The service design teacher leads the process and structures the week. Otherwise, all teachers have two roles. First, they facilitate groups according to their professional backgrounds. Second, they give informative presentations about specific subjects such as digital health and wellbeing, technology trends, different types of mock-ups, business models, project management, go-to-market plans and communication plans. These presentations give students deeper insight into the service design process. Another basic element of the course is strengthening the participants’ digital skills, and, therefore, the students are offered an opportunity to try low threshold basic coding. The intensive week also offers master students good opportunities to practice facilitating service design methods. Master or teacher students who participate as coaches get extra support for the facilitation from other teachers in the coaching team.

Roles of the Students

These studies are level 6 on the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) (European Union 2017/C 189/03). The student group can vary from 20 to 50, depending on the number of the schools participating and the amount of funds reserved for the exchange during the intensive week. The work is based on multiprofessional student groups that are planned prior to the intensive week. The participating students come from nursing, health promotion, physiotherapy, social services, business administration (BBA), IT security, IT business, IT engineering, doctors’ assistants and cultural design study programmes. The suitable number of students in a work group is five (health/social, business, service designers, IT) (Ahonen et al. 2018). In 2019, there were nine student groups. The students came from a multicultural context, which is one of the basic elements of the course (Ahonen et al. 2018).

Recruitment of the Industry Partners

One of the key elements of the programme is the recruitment of the industry partners. The industry partners will provide real-life challenges from their everyday work experience for the student teams to solve with innovative ideas.

The industry partners can be:

- Health-care service providers (private and public hospitals, outpatient care centres, elderly care centres, dental care clinics, etc.) with an interest in digital health solutions.

- Private companies developing various products and services for the health-care sector.

- Start-up companies focusing on the health-care sector.

- Consultation agencies providing, for example, product or service design services for the health-care sector.

The challenges provided by the industry partners set the theme and context for the student teams. This is why we suggest that the industry partners give a clearly formulated example and challenge/problem statement. Listed below are some examples of potential challenge statements:

- Provide a solution for early detection of migraine. The team can focus either on children or on adults.

- People use Google to search for what might be wrong with their health. This is often ineffective and can cause harm as people might buy and take unnecessary medications or other treatments. Therefore, design a reliable, user-friendly and effective way to use digital tools for self-assessment.

- The current cast used for fractures is uncomfortable for the patient. The cast makes the skin itchy and it is not removable. Provide a solution for better fracture treatment.

The examples show how the formulation of a challenge can vary from superficial to a very detailed and specific description. The level of complexity depends on many aspects such as the students’ skills in digital health, the available companies in the region, etc.

During the programme, the industry partners provide either face-to-face or online support for the students in the company’s operating field. In addition, the representatives of the industry partners evaluate the final presentations of the student teams and give them constructive feedback. It is not a goal for the student teams to continue their project together with their industry partner after the intensive course, but in case this happens, the academic team should support the student team by providing them with relevant resources (Klaassen 2018).

Service Design Week

The World Design Organization (WDO) has stated, “Design is a creative activity whose aim is to establish the multi-faceted qualities of objects, processes, services and their systems in whole life cycles. Therefore, design is the central factor of innovative humanization of technologies and the crucial factor of cultural and economic exchange” (Björk and Ottosson 2016). Design inspiration for the structure of the week comes partially from Google Ventures Design Sprint (Knapp et al 2016, Banfield et al 2015), but it has been developed much further based on the needs and prior experience of the facilitators.

The overall programme consists of the following: 1) Pre-assignment, 2) Intensive week, 3) Personal reflection report.

The purpose of the Pre-assignment is to get students orientated towards the subject and briefly introduce the main concepts and tools for the week. We send the following pre-assignment about one week before the intensive week for orientation:

As a pre-assignment, please familiarize yourself with the following material before our intensive week:

- Take a look at this video, which describes what service design is: https://vimeo.com/212939377

- Take a look at this video regarding how service design has been used in the health-care context: https://youtu.be/3e2urSZUorc

- Read this article, which will help you understand service design basics and process: “Design Thinking as an Effective Toolkit for Innovation” (Tschimmel 2012): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236135862_Design_Thinking_as_an_effective_Toolkit_for_Innovation

- Look at this webpage, which will introduce you to a useful tool for visualizing, developing and communicating complex processes: “What is a Swimlane Diagram” by Lucid Software Inc.: https://www.lucidchart.com/pages/swimlane-diagram#discovery__top

- Take a look at this video, which explains how to create paper prototypes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85muhAaySps

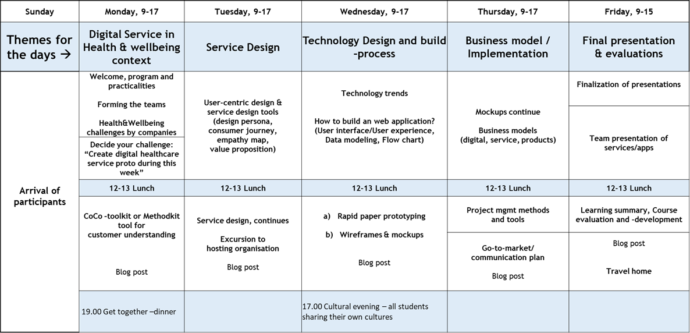

Intensive Week (Muddie Week) or design sprint week consists of five days, which all have their own themes as follows: 1) digital service in a health and wellbeing context, 2) service design, 3) technology design and build process, 4) business model and implementation and 5) final presentation and evaluation. Design week scheduling is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Muddie Design Week’s daily schedule

Figure 1. Muddie Design Week’s daily schedule

The service design process has three phases: 1) analyse to understand the problem, 2) concepts and 3) prototyping. There are tools for all phases, and common best practice tools were used during the week. Templates as a part of the best practice tools gave a structure to the design process. Templates and tools were also used to give multiprofessional and multicultural groups a common goal for working together. Each day had its own templates (e.g. Day 2: User-centric design & service design tools, including design persona, consumer journey, empathy map and value proposition canvas). Service design tools and templates with a creative commons licence are widely available on the Internet, for example: http://www.servicedesigntools.org/; https://www.thisisservicedesigndoing.com/methods and https://leanservicecreation.com/canvases.

Prototyping is an effective method for co-creation, communicating and getting feedback on ideas. Usually, the starting point is sketches on paper, and once an idea is somewhat “stabilized”, then either PowerPoint/Keynote-templates or online tools will help to create more visual presentations and even clickable mock-ups/prototypes of digital services. Online tools can be, for example, Figma.com, marvelapp.com, balsamiq.com, Adobe XD or, more generally, Miro.com or Canva.com. If the service is part of a physical service process, Legos and videos shot with a smartphone, for example, can also be used to visualize and effectively communicate the customer/patient process.

Coaching is required at all times, and, in the best case, there are always available coaches who are teachers with different backgrounds (service design, health care, IT). Company partners’ participation is required on Monday for the challenge briefings and on Friday for hearing the potential solutions and commenting on them. In the best case, the company participants are available daily for guidance, preferably face-to-face but at least via phone, mail or Slack/other digital channels.

At the final presentation to the companies, a jury is set for evaluating the teams and creating a spirit of competition, making sure students try their best. The jury consists of coaches and customers who evaluate the teams (Figure 2) based on common criteria.

Figure 2. Dimensions for evaluation

Figure 2. Dimensions for evaluation

Teams are evaluated according to the following three criteria: 1) best solution, 2) best progress during the week (e.g. for an especially challenging assignment or a team missing a key competence) and 3) best teamwork. Each of the criteria is evaluated from one to five by each member of the jury. The evaluation is also always based on dialogue and active communication among participants of the jury. Often, several teams can be announced as winners.

Students also write personal reflection reports. After the intensive week, during which students have been overwhelmed with new information, challenging assignments, team dynamic challenges and working in a truly cross-cultural and interdisciplinary environment, students are given one week to reflect on two simple questions:

a) What did you learn during the intensive week? (No need to repeat what you did.)

b) What would you do differently on the next round?

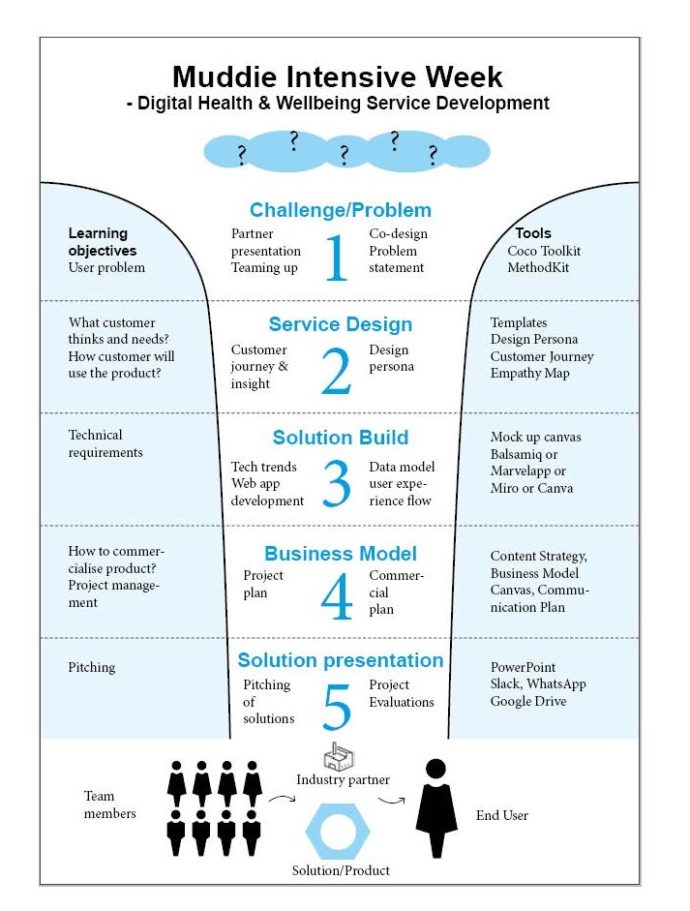

This assignment usually sparks a deep thinking process and metacognition on student’s learning and critical reflection on what and how to behave differently on a personal level (there is no longer any possibility to think about how the team worked, since that is often given; the only thing they can truly affect is themselves, which will affect the team dynamics). Student evaluation consists of four elements: 1) self-evaluation during the whole process and the personal reflection report after the intensive week; 2) group evaluation among group members regarding communication and the productive work of each member of the group; 3) industrial partners’ evaluation of the group’s product at the end of the week and 4) teachers’ evaluation of each student’s work in the group during the process, of the product and of the students’ reflection reports. All these combined elements frame the students’ evaluation based on EQF level 6 (Eu 2017/C 189/03). Figure 3 describes the model of the intensive week.

Figure 3. Service Design Innovation Model for Higher Education in the Context of Digital Health and Wellbeing

Figure 3. Service Design Innovation Model for Higher Education in the Context of Digital Health and Wellbeing

This section has described the main phases and contests of our intensive week. The service design week can also be seen as an innovation model for higher education multiprofessional co-creation work. In our intensive week, the content came from the context of digital health and wellbeing.

Student Feedback

The week was filled with collaboration, skill-sharing, learning and networking, all of which will be beneficial for the future.

A student of nursing commented:

“The intensive week in Riga was my first experience with multiprofessional work. I must to say that it was an unbelievably valuable experience for me as a health-care professional and also for improving my personal skills. The intensive week required hard work and maximum concentration and creativity, being open-minded and productive while working with new information. The Muddie Week was a big challenge for me not only because of different goals, tasks and periods, but due to differences in cultures, competencies and communication levels of participants. I feel that this experience has helped me understand the different values and possibilities, which I might encounter in my future career and in the future of health care in general. I am going to use the skills I learned in my future studies and working environments, using design thinking methods and other tools which we were introduced to in Riga. They have showed me how narrow-minded I am on many practical and theoretical points.”

“ Another valuable aspect of the intensive study week was the constant presence of coaches. We could get advice, tips and consultations from professionals in each field, including the fields of medicine, design, security, IT, social services and business. The coaches were inspiring, directing and supporting us before, during and after the trip. The teachers did not distance themselves from the students and were happy to answer all our questions.”

“Due to time limitations, we felt stressed sometimes, but that just gave me an insight to how the development of projects happens in real life. My Muddie Week team had nursing students, a social services student and a business student. After five days of brainstorming with those wonderful individuals, I am sure that the phrase ’together we are stronger’ is true, because only in multiprofessional working environments would we be able to find and develop solutions for the proposed challenge. As for me, there is no way back—we are here to make changes. I am infinitely thankful to be given the chance to participate in the DEDIWE course and the Muddie Intensive Week. I have never felt so inspired and purposeful in my life.”

A student of business management offered this feedback:

“I found it very interesting. It was challenging at first to come together and work with people from different fields. Fields ranged from business and IT to nursing, but we managed to find common ground in the end. The facilities were fantastic.

“We were given the opportunity to familiarize ourselves with companies who provided the cases as well as learn about working life in Latvia. I found this to be extremely beneficial. We were also able to network during the week. I might even use the representative from the company Digital Brand as a contact in the future. Learning how companies in Latvia network proved to be useful.”

“The companies as well as the cases provided were all different. Lectures based on the cases were informative and to the point. I especially enjoyed the IT lecture, which was given by a lecturer from Arcada UAS. He had well-thought-through examples, and he provided us with a different point of view on the subject.”

Another student of nursing offered the following comments:

“One more chance to engage in multicultural environment and come to terms with a group of people and argue my point of view. Opened a new horizon on apps—they are created by multidisciplinary teams, all working for one goal from different perspectives. I would like to participate in creating apps for the health sphere by helping to make them comfortable and user-friendly. I think I might have ideas.”

A student from the Administration of Arts Institutions study programme said this:

“From now on, I will try my best to not be afraid of expressing my own thoughts and opinions, because I learned that even if I’m not experienced in a certain field, my opinions sometimes can help to decide, and I can help others to see from a different perspective. In addition, I learned a lot about nursing, IT and business that might be helpful in the future. The teachers were great and didn’t hesitate to help.”

A student of IT offered this feedback:

“I think the teamwork was really quite good. I was happy that our company representative was able to give us more information about our company. I think the interaction was good; however, some of the clients could have better managed their time and presentations, as we went into overtime. I learned a lot about doing design sprints, and I think that almost everything we did was relevant and useful for future work.”

Summary

Our society needs multiprofessional and multidisciplinary competencies to build up functional e-services for the health- and social-care sector. There are many laws and regulations that need to be taken into account when building up new services for health and social care. At the same time, we need multidisciplinary service design processes to bring multiprofessional perspectives to the service design processes and to take customers’ journeys to the middle. Customers themselves should also be allowed to be active partners of the design process.

The purpose for this description of the multidisciplinary intensive week has been to give readers one example of how to coordinate studies for a multiprofessional and multicultural group of students. Creating partners out of teachers and students from health and social care, IT and service design backgrounds has great possibilities for increasing knowledge around eHealth and welfare services. Multidisciplinary skills are very important in today’s working life because we need to orchestrate and take part in the development of the culture to digitalize different sectors of society with many stakeholders (Björk & Ottosson 2016; WHO 2018).

References

- Ahonen, O., Tana, J., Lejonqvist, G-B., Mahla, M., Marnauza, S., and Rajalahti, E. 2018. “Case Study: The Development of Digital Health and Welfare Services in Estonia, Finland and Latvia. EU*US eHealth Work Project’s Global Case Studies.” Chicago: HIMSS. https://www.himss.org/professionaldevelopment/development-digital-health-and-welfare-services-estonia-finland-and-latvia.

- Banfield, R., Lombardo, C. T., and Wax, T. 2015. Design sprint: A practical guidebook for building great digital products. O’Reilly, Sebastopol, CA.

- Brown, T. 2008. “Design Thinking.” Harvard Business Review June: 85–92.

- Björk, E., and Ottosson, S. 2016. “Cross-Professional Cooperation in a University Setting.” Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 229:10–20. Design Research Portal (2013). https://designresearchportal.wordpress.com/2013/11/05/icsids-definition-of-design/.

- European Commission. 2012. “eHealth Action Plan 2012-2020. Innovative Healthcare for the 21st Century.” http://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/news/ehealth-action-plan-2012-2020-innovative-healthcare-21st-century.

- European Commission. 2013. “ICT for Societal Challenges.” https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/ict-societal-challenges-new-publication-research-and-innovation-projects.

- Euroopan Unioni (2017/C 189/03) NEUVOSTON SUOSITUS, annettu 22 päivänä toukokuuta 2017, eurooppalaisesta tutkintojen viitekehyksestä elinikäisen oppimisen edistämiseksi ja eurooppalaisen tutkintojen viitekehyksen perustamisesta elinikäisen oppimisen edistämiseksi 23 päivänä huhtikuuta 2008 annetun Euroopan parlamentin ja neuvoston suosituksen kumoamisesta (2017/C 189/03). (viitattu 19.3.2019) Saatavilla: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FI/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2017:189:FULL&from=EN.

- Gaskell, A. 2018. “Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver A Digital Future.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/adigaskell/2018/11/09/preparing-the-healthcare-workforce-to-deliver-the-digital-future/#1f786f346d34.

- Gordon L. 2018. “Assessment of Smart Watches for Management of Non-Communicable Diseases in the Ageing Population: A Systematic Review.” Geriatrics (Basel, Switzerland) 3(3): 56. doi:10.3390/geriatrics3030056.

- Granja, C., Janssen, W., and Johansen, M. A. 2018. “Factors Determining the Success and Failure of eHealth Interventions: Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 20(5), e10235. doi:10.2196/10235.

- Jiang, F., Jiang, Y., Zhi, H., Dong, Y., Li, H., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Dong, Q., Shen, H., and Wang, Y. 2017. “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Past, Present and Future.” Stroke and Vascular Neurology 2(4), 230–243. doi:10.1136/svn-2017-000101.

- Knapp, J., Kowitz, B., and Zeratsky J. 2016. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days. Simon & Schuster.

- Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on Medical Devices.

- Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices.

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data.

- Pulkkis, G., Karlsson, J., Westerlund, M., and Tana, J. August 2017. “Secure and Reliable Internet of Things Systems for Healthcare.” In 2017 IEEE 5th International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud (FiCloud), pp. 169–176. IEEE.

- Sabesan, S., Larkins, S., Evans, R., Varma, S., Andrews, A., Beuttner, P., Brennan, S., and Young, M. 2012. “Telemedicine for Rural Cancer Care in North Queensland: Bringing Cancer Care Home.” Australian Journal of Rural Health 20: 259–264. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2012.01299.

- Strickland, E. 2019. “IBM Watson, Heal Thyself: How IBM Overpromised and Underdelivered on AI Health Care.” IEEE Spectrum 56(04): 24–31.

- Teso, G. , Ceppi, G. , Furlanetto, A. , Dario, C., and Scannapieco, G. 2013. “Defining the Role of Service Design in Healthcare.” Design Management Review 24: 40–47. doi:10.1111/drev.10250.

- Tschimmel, K. 2012. “Design Thinking as an Effective Toolkit for Innovation.” In Proceedings of the XXIII ISPIM Conference: Action for Innovation: Innovating from Experience. Barcelona.

- World Design Organization (WDO). 2017. “Board Report 2017–2019.” https://wdo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/WDO-BoardReport17-19.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2018. “Towards a Roadmap for the Digitalization of National Health Systems in Europe.” http://www.euro.who.int/en/countries/hungary/publications/towards-a-roadmap-for-the-digitalization-of-national-health-systems-in-europe.-meeting-report-2018.