Today, our world is more complex and interconnected than ever before. Diseases in one country are threats to all countries, and healthcare needs of people are universal. Nursing students must be culturally aware and culturally sensitive to all cultures, because as nurses they will provide care for all clients, regardless of their cultures and beliefs. Knowing their clients helps nurses provide better care and maintain a much more comfortable and relaxed environment, which will favour their clients’ speedy recovery.

Photo: C. Cagnin/Pexels

Photo: C. Cagnin/Pexels

Culture has a significant impact on nursing practice as empathy plays a key role there. Nurses need to understand their clients’ emotions, which are displayed in different ways in different cultures, e.g. Finnish people often downplay their emotions, whereas emotions are shown more openly in many other European cultures. Nursing students’ understanding of cultural differences can be enhanced through planned learning experiences in foreign countries, especially through undertaking a clinical placement abroad (Heuer & Bengiamin 2001).

This article explored the concept of “culture shock” as well as the theoretical background for the journey of a nursing student experiencing an exchange abroad. It was written by senior lecturer Sari Myréen, German nursing student Anna Hiebsch, Spanish nursing student Antía Castellanos Ferreiro and Polish nursing student Gabriela Blichowska who were exchange students in Finland. Anna Hiebsch also provided valuable tips for students planning an exchange abroad.

Experiencing a “culture shock” in a foreign country

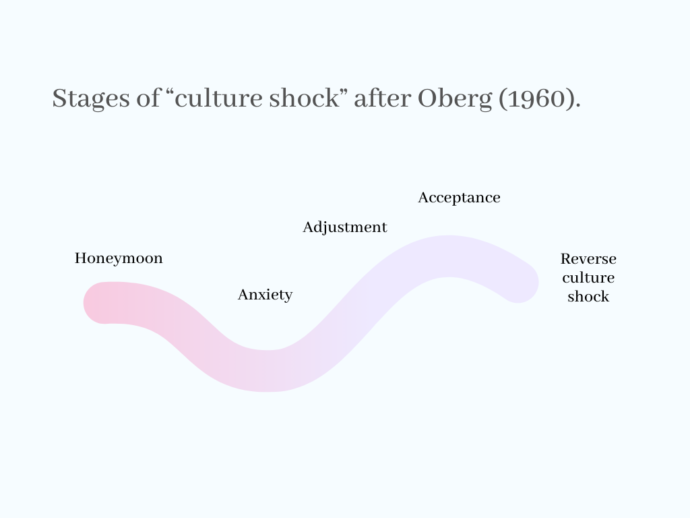

“Culture shock” can be defined as a feeling of disorientation experienced by someone who is suddenly subjected to an unfamiliar culture, way of life, or set of attitudes. Oberg (1960) identified four stages of “culture shock” and depicted it as a roller coaster ride with its lows and highs when subjected to a new culture (see Figure 1). In the euphoric stage, we are fascinated by the new surroundings. In the second stage, irritability and hostility, frustration and disappointment take place. In the third stage, we gradually begin to adjust to the new surroundings and to the culture. In the final stage, i.e. adaption, we accept and appreciate the differences and similarities of the foreign culture. Reverse “culture shock” refers to the difficulty to re-adjust back into one’s own culture after a long period of time in a different culture.

Figure 1. Stages of “culture shock” after Oberg (1960). (Myréen 2022)

Figure 1. Stages of “culture shock” after Oberg (1960). (Myréen 2022)

Current research papers have proposed alternative perspectives on “culture shock”. Fitzpatrick (2017) challenges the notion of culture as an essential, reified concept, arguing that “culture shock” is not about culture, but about the dynamics of context and how individuals deal with life changes to navigate the challenges that they face. He seeks an underlying paradigmatic clarification of the term “culture shock” from a social constructionist perspective on intercultural behaviour and thereby challenges the notion of “culture” as the cause of “shock” in international relocation.

The social constructionist perspective to social behaviour rejects the idea that culture can be reduced to stereotyped classifications such as nationality or ethnicity, and it defines culture through interactions among people. Culture is continuously evolving and adapting to the realities experienced by its members. Culture evolves and reshapes itself throughout the years; it is influenced by the interaction of its members with members of other cultures, and with their surroundings, by cultural and economic exchanges and by globalisation. (Georgescu et al. 2018.)

Ward, Bochner & Furnham (2001) developed an ABC model for “culture shock” by merging three main traditions in acculturation research. These are the culture learning approach, which focuses on the behaviours and social skills involved in acquiring the linguistic and cultural norms to be able to thrive in a new cultural milieu, and which can be influenced by such factors as length of residence, previous experience abroad and cross-cultural training. Second, the stress and coping approach presents cross-cultural transition as a psychological process of coping with the stress that can accompany substantial life changes, influenced by aspects of individual coping styles, personality, locus of control, tolerance of ambiguity and how individuals deal with homesickness or loneliness. Third, social identity theories focus on cognitive elements related to theories of identity and traits that can be tested psychometrically to monitor adjustment.

Psychological adjustment is dependent on personality factors, such as a tendency to extroversion and the desire to seek contact with other people in the initial stages, or a strong internal locus of control or an ability to cope with change. Whereas sociocultural adjustment is much more subject to behavioural responses which affect the attainment of social skills extant within the new cultural environment, including, for example, learning a new language or adjusting to unfamiliar behavioural norms. In this sense, it can be contended that sociocultural adjustment may improve as a result of the length of a sojourn and the amount of interface and interaction with the local population. (Ward, Bochner & Furnham 2001.)

Ward’s & Kennedy’s (2001) findings on cross-cultural coping strategies are consistent with the broader stress and coping literature, i.e. direct, task-oriented strategies (e.g., planning and active coping) and the use of humor are associated with better psychological adjustment, whereas avoidant responses (e.g., disengagement, denial, venting) are related to greater psychological distress. “Culture shock” is an inevitable aspect of international clinical placements. Planning, preparation and support are required from facilitators to ensure that students assimilate into the new culture and to maximise their learning experience abroad. Support by the facilitators is essential to help students to adjust and adapt to “culture shock” and to increase their learning opportunities (Maginnis & Anderson 2017).

International experiences through semesters abroad

Advantages of an international experience for nursing students include the opportunities to live, even for a short time, in a different country in order to become aware of the importance of cultural factors that impact health care delivery, to experience the influence of history and culture on the development and function of a country’s healthcare system, to recognise cultural influences that affect the citizens’ views about health and illness, and to observe the day to day functioning of a different health care system, especially the delivery of health care in community settings. These opportunities are, however, often accompanied by challenges to both the student participants and their preceptors for the clinical part of the experience. (Egenes 2012.)

It is important for incoming international nursing students to familiarise themselves with the nurse’s job description and duties in the receiving country prior to their clinical placement. International students’ self-confidence and knowledge of clinical placement requirements will also increase through language and culture related education prior to their clinical placements. (Mikkonen, Elo, Kuivila, Tuomikoski & Kääriäinen 2016.)

International nursing students need time and support from their preceptors in order to help them adapt to the clinical environment, and orientation into these clinical environments promotes their integration. But regardless of how amazing their mentors are, some things are out of the mentors’ hands. The student’s own role and attitudes also influence the nature of their learning experience in the clinical environment.

Students often experience adaptation to a new cultural context as challenging and stressful because it involves uncertainty, fear and helplessness. Adaptation takes time and students need targeted support especially during the beginning of clinical placements. However, adaptation to a new cultural environment can also be a very rewarding learning experience. Students will identify and compare cultural differences, which helps them in developing acceptance towards other cultures. (Mikkonen, Elo, Kuivila, Tuomikoski & Kääriäinen 2016.)

Being open to everything is the best way to get to know and learn, if you are not used to the culture. You may see many differences compared to your home country, but there is one important aspect about the differences. We are all individuals and wherever you are, there will be something different, strange and new for you, but this gives the possibility to learn and experience also something new. You should be open to all the new things and just take in all of the experiences you can get during your stay. With this your internship or semester abroad will have many highs, but maybe also a few lows.

International clinical placements provide opportunities to engage nursing students in cultural awareness and increase their responsiveness through cultural immersion. International clinical placements do not occur without challenges and one challenge many students experience when undertaking an international clinical placement is that of “culture shock”.

In my opinion providing emotional support is the most important aspect. To have the knowledge about a specific culture will not always help you to avoid the cultural shock, because especially during the time of being abroad, the culture will be experienced differently. Even though you know about differences, to experience it and live in the country can nevertheless catch you unexpected and overwhelm you. In this case, it is important to have someone reliable and trustworthy person to talk to about everything that you want or feel the need to talk about. It might be helpful to prevent the fear and anxiety beforehand with knowledge, but it still can cause negative feelings and in this situation you should have support.

The opportunity to undertake an international clinical placement increases cultural awareness, sensitivity, competence and respect for another culture. Preparation prior to departure is essential focusing on the difference in culture, health care system, expectations of nursing students and their role. Support from the facilitators is essential and the students must be fully informed about the destination as well as about their role and responsibilities there.

Development of cultural competence is an outcome of any international clinical placement. The process to gain an awareness of this concept ultimately includes a “culture shock” experienced to varying degrees by all participants. The aim for the facilitators in the process is to minimise the amount of “culture shock” and to support students through this process maximising their learning experience. (Maginnis & Anderson 2017.)

Recognising and accepting differences

Even a short-term international programme might provide the necessary tools for nursing students in today’s world. Such programmes may be used to build a foundation that establishes the framework of invaluable cultural knowledge and skills when nurses are caring for culturally and linguistically diverse people. (Heuer & Bengiamin 2001.)

Care for Europe is an Erasmus+ KA2 Strategic Partnerships project, which aims to internationalise nursing courses through a better integration of incoming nursing students during their clinical placements, and its partner institutions are the French Red Cross IRFSS Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes in France, University of Pécs in Hungary, Universitat de Lleida in Spain and Laurea University of Applied Sciences in Finland. They will have an opportunity to send five students from each institution to an intensive summer school in France, which will combine interculturality and simulation. In the summer school, the theoretical content on interculturality will be supplemented and enriched by workshops and simulation sessions, where the participants will work in multicultural teams, and which will be based on the scenarios developed by the project partner institutions. As for the study unit Cultural awareness and intercultural communication in healthcare professions at Laurea University of Applied Sciences, it will include preparatory assignments on cultural awareness and intercultural communication in healthcare professions to support and maximise the students’ intercultural learning experiences during the summer school. The summer school will finally provide discussions on interculturality awareness as well as comparisons on nursing care in the project partner countries, thus offering a unique opportunity for students to adapt to a new cultural context through multicultural encounters and workshop activities.

Traditionally, it has been thought that in multicultural encounters, it is essential to know different cultures on the basis of their general and external criteria. Today, health care is confronted with many different cultural groups and, increasingly, people who represent more than one cultural group at a time. There can also be great differences within the same culture. Professionals have less time and resources to learn about the practices and beliefs of different cultural groups. In addition, cultures are constantly changing, making it very difficult or impossible to identify all the typical characteristics of a particular culture. (Mikkonen et al. 2021.)

Finally, it feels important for me to highlight the diversity and individuality of humans. No matter what background people have, it’s always important to see a person as an individual. The cultural background will affect them, but this doesn’t mean that people with the same culture are the same. Don’t stress yourself too much about learning the cultural differences, because this can also have side effects, but instead, ask and interact with people to experience their daily lives and culture. Everything will be new for you and you will learn from this diversity. A semester abroad has many highs, but maybe also a few lows. Nevertheless, I can recommend this unique experience that will open your eyes to the world and will be remembered forever.

The citations in the text are written by Anna Hiebsch.

References:

- Egenes, K. 2012. Health care delivery through a different lens: The lived experience of culture shock while participating in an international educational program. Nurse Education Today, Volume 32, Issue 7, 760-764.

- Fitzpatrick, F. 2017. Taking the “culture” out of “culture shock” – a critical review of literature on cross-cultural adjustment in international relocation. Critical perspectives on international business. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Georgescu, M. et al. (Eds.) 2018. T-Kit Intercultural Learning. Council of Europe and European Commission.

- Heuer, L. & Bengiamin, M. 2001. American nursing students experience shock during a short-term international program. Journal of Cultural Diversity 8(4): 128-34.

- Maginnis, C. & Anderson J. 2017. A discussion of nursing students’ experiences of culture shock during an international clinical placement and the clinical facilitators’ role. Contemporary Nurse: a Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession 53(3): 348-354.

- Mikkonen, K. et al. (Eds.) 2021. Advanced Mentorship Competences, Modules I – III of Advanced Mentorship Competences. Retrieved at: https://www.qualment.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Advanced_Mentorship_Competences_QualMent_final.pdf

- Mikkonen, K., Elo, S., Kuivila, H., Tuomikoski A. & Kääriäinen M. 2016. Culturally and linguistically diverse healthcare students’ experiences of learning in a clinical environment: A systematic review of qualitative studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 54: 173-187.

- Oberg, K. 1960. Cultural Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments. Practical Anthropology. 7(4): 177-182.

- Ward, C., Bochner, S. & Furnham, A. 2001. The Psychology of Culture Shock. Routledge, London.

- Ward, C. & Kennedy, A. 2001. Coping with Cross-Cultural Transition. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 32(5): 636-642.