Strengthening Europe’s security requires more than research results on paper — it demands solutions tested, demonstrated, and adapted to real operational needs. At the CERIS Joint Demonstration Event in Turku, EU-funded innovators and practitioners came together to bridge this gap, showcasing technologies that enhance border surveillance, maritime situational awareness, and the protection of critical infrastructure. Among them, the VIGIMARE project’s Virtual Control Room stood out as an example of how European collaboration can turn advanced research into practical capabilities.

Me at our exhibition stand at the event. Photo by Tiina Haapanen 2025

At the beginning of September, I travelled to Turku, Finland, for a Joint Demonstration Event on European innovation in border surveillance, organised under the CERIS (Community for European Research and Innovation for Security) umbrella by DG HOME, the University of Turku, Turku University of Applied Sciences, and the Finnish Border Guard. Unlike a traditional conference, this event brought together researchers, companies, and practitioners to showcase and test new solutions in a hands-on format. Together with my VIGIMARE project colleagues from Laurea (Minna Markkanen, Tiina Haapanen, and Jari Räsänen) and our technical coordinator from RISE (Research Institutes of Sweden), we demonstrated the Virtual Control Room (VCR) , an AI-based platform for real-time anomaly detection and shared situational awareness, developed in the Horizon Europe projects AI-ARC and VIGIMARE, while also experiencing first-hand how DG HOME and CERIS are creating new ways to connect EU-funded innovations with their future users.

From Policy to Practice: A New Type of EU Demonstration Event

This was not a standard policy meeting or a research project review. Instead, it was a new type of event where innovators from EU-funded projects were invited to demonstrate their solutions directly to the people who might one day use them in practice: members of the European Border and Coast Guard (EBCG), national border authorities, Frontex, and other European agencies. The idea was to bridge the gap between project outcomes and real operational needs — something I believe is absolutely crucial if EU investments in innovation are to have a lasting impact.

The demonstrations covered a wide range of capabilities: situational awareness at sea and on land, counter-drone systems, data fusion and analysis, sensors, and autonomous systems. All of them were shown in a very hands-on way, through interactive use cases and scenarios, which made the whole event dynamic and practical. In addition, we were given the opportunity to visit the Regional Coast Guard Control Room and Training Centre in Aboa Mare, which gave a fascinating and very positive insight into how end users work and train in real-life operational environments.

Presentation by the Finnish Coast Guard at Regional Coast Guard Control Room in Aboa Mare, Turku. Photo by Johanna Karvonen 2025

Showcasing the Virtual Control Room

Our solution was selected as one of the demonstrators at the event and we got the opportunity to present the Virtual Control Room (VCR), an AI-based platform we have been developing in recent years. The VCR detects, analyses, and visualises anomalies in real time, and also offers shared situational awareness through Virtual Reality. It brings together multiple data sources, applies reliability checks to filter out false alerts, and can be used anywhere — there are no geographical limitations.

What makes the VCR exciting is its flexibility. It was originally developed in the Horizon Europe project AI-ARC (2021–2024), where we tested it together with the Swedish and Icelandic Coast Guards, even on live vessels. Its applications range from detecting dark vessels and smuggling activities to protecting subsea cables, monitoring vessel traffic, and even environmental reporting (for example, pollution or ice conditions reported directly by civilians at sea).

- Dark vessels are ships that deliberately switch off or disable their Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmissions to avoid detection. The AIS is a GPS-based tracking system mandated by the International Maritime Organization for large vessels, which continuously broadcasts data such as the ship’s identity, type, size, location, course, and speed every few seconds. By “going dark,” these vessels evade standard tracking systems and may engage in unreported fishing, smuggling, or other illicit maritime activity (Science Learning Hub, 2020).

VIGIMARE’s Technical Coordinator, Pontus Svenson, during our demonstration. Photo by Johanna Karvonen 2025

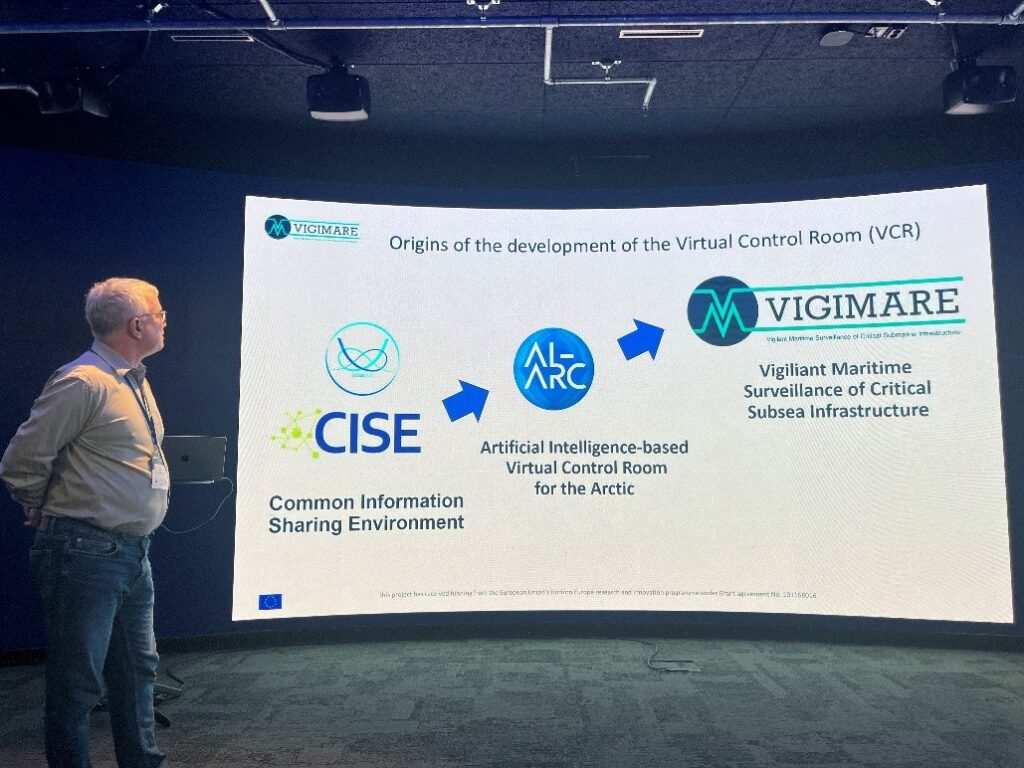

From Arctic Safety to Subsea Security: The Evolution of the VCR

After the Nord Stream sabotage in 2022, the need to better protect submarine infrastructure became urgent. The development of the Virtual Control Room (VCR) had originally started in the Horizon Europe project AI-ARC (ai-arc.eu), which was primarily focused on security for mariners operating in the harsh conditions of the Arctic Sea. However, as the Nord Stream attacks took place during the lifetime of AI-ARC and the early stages of the VCR’s development, the relevance of monitoring and protecting submarine critical infrastructure became increasingly clear. Services we had begun designing for maritime safety were adapted to support this wider security need, and the scope of the VCR shifted accordingly. Out of this evolution, the VIGIMARE project (vigimare.eu) was established, with the explicit aim of further developing and testing the VCR for the protection of subsea infrastructure. In VIGIMARE, the platform is being enhanced with new data sources, both above and below the surface, and its geographical scope is expanding from the Arctic to the Mediterranean and North Sea, with the potential to scale to any maritime region.

Lessons Learned and the Road Ahead

For me, the Turku event was not just about showcasing technology, it was mainly about listening and learning from practitioners. Their feedback helped us understand what features are most useful, and where the gaps still are. It also reminded me of the importance of continued funding and testing. For the VCR to reach full operational readiness, we estimate that at least a year of operational tests are needed. The Gulf of Finland/North Baltic Sea would be an ideal testing ground: compact in size, with heavy vessel traffic (including the Russian shadow fleet), strong radar and sensor coverage, and conditions that allow us to test in both summer and winter.

Events like this matter. They create a rare but vital meeting point between research and practice, and they show how European collaboration can directly strengthen our security and resilience. For us, demonstrating the Virtual Control Room in Turku was an important milestone and a step closer to bringing this innovation into real operational use.

The language editing and structure for this text has been improved using Copilot.

References