The challenges changemakers seeking to have an impact on society are increasingly broad, difficult to define and solve by individual actors. To be better at tackling these systemic challenges, we have to innovate how we innovate by shifting efforts from developing parts to fostering partnerships. This article elaborates on discussions at the Waves Summit 2024 regarding the polycrisis and systemic investing and their relevance to Laurea’s work on innovation management and ecosystems.

Photo by Mikael Seppälä/DALL-E

Photo by Mikael Seppälä/DALL-E

ChatGPT was used in writing of this article by summarizing event notes done by the author and enhancing the fluency of the English language. The author is responsible for the content.

Ferrigno, Crupi, Di Minin and Ritala (2023) explored the 50-year historical development of R&D based on articles in the R&D Management academic journal. One of their findings was that the context of R&D has been broadening. The recent years have seen a shift in the context of R&A where the firm-centric view has increasingly been extended by perspectives related to global disruptions (f.ex. climate change, wars, and pandemics) and the need to promote sustainability. (Ferrigno et al. 2023.)

This topic was the focus of the Waves Summit – Forum For Changemakers in Helsinki in April 2024, which I had the opportunity to attend. The Summit featured many leading international and national speakers. In this article I will introduce some of the ideas that inspired me personally and are relevant to my work in coordinating the innovation management and ecosystems theme team at the Laurea University of Applied Sciences.

The polycrisis challenges our notion of innovation

One of the speakers I was most looking forward to hearing was Daniel Schmachtenberger. He is the founder of the Civilization Research Institute (CRI) think tank. Its focus is in helping humanity avoid global catastrophic risks. Examples of these are governing exponential technologies and doing what is needed to keep planet sustainable. The core of Schmachtenberger’s (2024) fireside talk at the Waves Summit were the concepts of polycrisis, metacrisis and their implications for how we innovate.

According to him the polycrisis can be described as the convergence of multiple, interrelated global crises. Therey are complex, entangled, and thus very difficult to tackle. These crises are cross-domain and operate in the range of environmental, economic, political, technological, and social issues. An individual crisis is troubling, but the entanglement of multiple crises effects by which they amplify each other. (Schmachtenberger 2024.)

Schmachtenberger (2024) used the concept of metacrisis to describe the mental models and other systemic fundamentals from which the polycrisis has emerged. At the heart of of the challenges are our current socio-economic, political and cultural paradigms. The metacrisis can be understood through the inadequacies of our institutions, governance systems and collective sense-making in dealing with the complexity related to the polycrisis.

The practical implications of Schmachtenberger’s (2024) talk was the need to renew the fundamentals by which we think, govern and organise society: we have to innovate how we innovate. He mentioned the importance of designing solutions not in isolation but rather as an ecology of solutions. The different solutions should work together in tackling a larger system of regulatory issues, technological development and cultural change. The ecology of solutions should seek to reflect the entanglement and amplification of the challenges at hand. In addition to this the solutions should be designed so that they minimise harm and seek to create plentiful rippling benefits across the systems.

My key takeaway from Schmachtenberger’s talk at the Waves Summit was to understand the broader context of the challenges changemakers face today and use that to renew the fundamental ways we develop solutions.

Partnerships are at the heart of transformative innovation

So the practical question is: how should we innovate to address the polycrisis? Many talks at the event highlighted that partnerships and the skills and capabilities that underpin them are key to innovating the current complex global context.

In the “From Super Heroes to Social Movements” panel Jan Artem Henriksson (2024) of the Sweden-based Inner Development Goals organisation made the important point that changemakers need to move from being activists to being collaborators and partners with those they want to influence. According to Henriksson activists are not necessarily successful because they judge and condemn those who do not share the same values as activists. Instead, they should rather collaborate and build bridges with them. In addition to the skills needed to be able to do this, it also requires possible shifts in internal conditions. This is where he states the Inner Development Goals seek to offer help through five themes and a set of practices that relate to each theme. Henriksson introduced the five themes of Inner Development Goals, which are :

- nurturing a healthy relationship with oneself (BEING)

- enhancing cognitive skills for better thinking (THINKING)

- fostering care for others and the world (RELATING)

- developing social skills for effective collaboration (COLLABORATING), and

- taking actions that enable positive change (ACTING).

But where and how could these themes and practices be applied to deal with the scale of the challenges of our times as the can not be solved within the relationships we all live in? Dominic Hofstetter, the Executive Director of the TransCap Initiate, highlighted systemic investing in supporting transformative innovation as a practical way of implementing Schmachtenberger’s idea of an ecology of solutions.

Systemic investing fosters the conditions for multi-organisational collaboration

One of the questions explored in the event was how to purposefully combine different forms of capital in tackling the polycrisis through fostering just and sustainable societies. The ”Financing systems are changing – how can our financing models enable systemic impact?” panel featured Hofstetter, impact investor Annika Sten Pärson of The Inner Foundation and entrepreneur Jimmy Westerheim of The Human Aspect. The panel hosted presentations from all three and a short discussion.

According to Hofstetter (2020) systemic investing is emerging as an approach to deploy capital with the intention of catalysing directional, transformative change in socio-technical systems. The approach combines systems thinking with investment practice and introduces systemic investments as economical vehicles that might help enable sustainability transitions in complex adaptive systems.

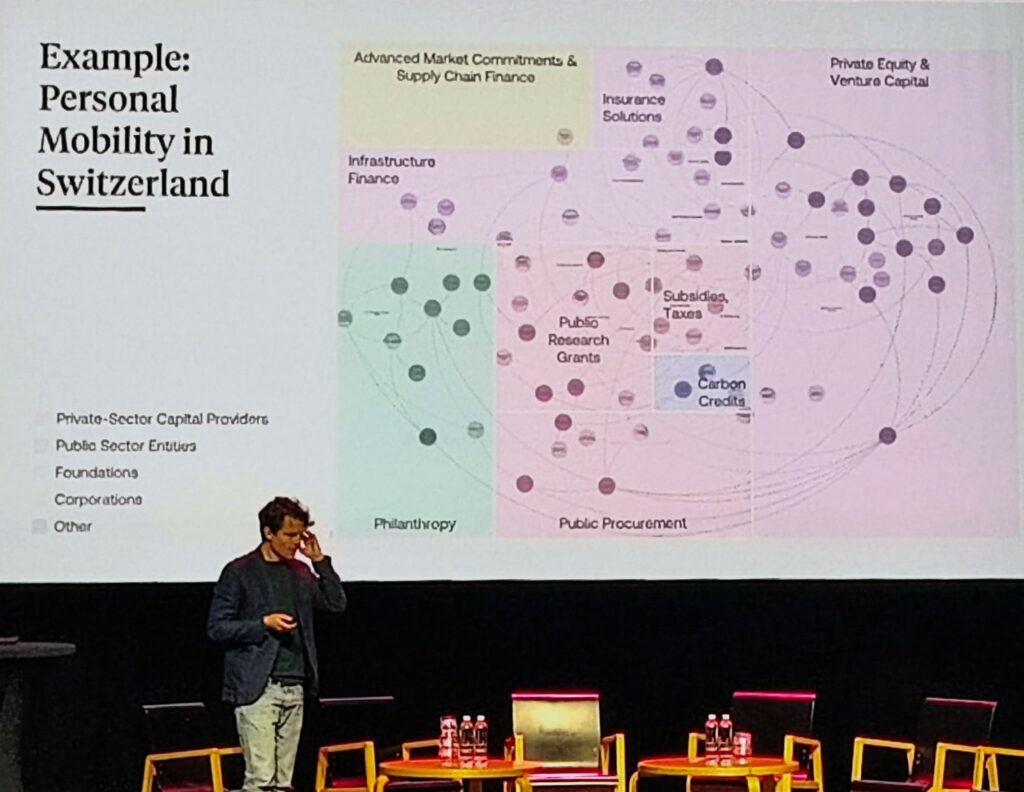

Hofstetter (2024) criticised traditional finance of often preferring isolated, technological solutions. To make his point he gave the example of how the ongoing shift in propulsion from petrol to electricity has not been able to solve the systemic challenge of traffic congestion. Systemic problems are not solved in isolation but through joined-up efforts orchestrated in partnerships, a practice central to systemic investing. Another aspect of the approach is extending investment timeframes from the short-term to 10-15 years. This is done to foster investments that can operate at the timespans needed for the necessary transitions to happen and make a lasting impact in the systems the systemic investments seek to support.

Hofstetter (2024) mentioned the aspect of developing funding architectures able to strategically align capital with the timing and needs of different initiatives that seek to help systems change. The funding architectures should be able to offer the right type of capital at the right time in right ways. This is done to help combinatorial and synergetic effects happen by composing innovation experiments that work and learn together. This thought is very close to the idea Schmachtenberger mentioned regarding developing an ecology of solutions.

For systemic investing to work, capital partnerships are not the only required resource. In addition to this type of investing should embrace creating an understanding of the systems in question especially in terms of identifying capabilities missing from the systems and hindering its effective functioning. For example research, field building, prototyping interventions and coordinating the systems might be supported by capital. Whereas traditional finance invests in solutions, the different forms of capital in systemic investing operates in relation with the practitioners and partnerships working in the systems. This requires creating collaborative innovation spaces where the exchanges can happen.

Picture 1. Dominic Hofstetter presenting an outline of multiple forms of capital identified to shift the different parts of the personal mobility system in Switzerland. (Photo: Mikael Seppälä).

Picture 1. Dominic Hofstetter presenting an outline of multiple forms of capital identified to shift the different parts of the personal mobility system in Switzerland. (Photo: Mikael Seppälä).

Hofstetter (2024) also spoke of the TransCap Initiative that is an organisation and collaborative innovation space which seeks to develop, experiment with and scale the practice of systemic investing. The TransCap Initiative has a bold development pathway where they seek to be able to manage millions (in terms of currency) in the early stages, connecting billions in the scaling phased and, in time, inspire trillions when the approach becomes the new global normal.

Hofstetter’s (2024) purpose for the next 10 years is to develop systemic investing to where impact investing is today. Whereas impact investing is often implemented by individual organisations, funding partnerships are at the heart of systemic investing. They are very important because in addition to connecting the doers, subject-area experts from multiple fields, connecting the funders representing multiple different financial instruments helps create the conditions for the doers.

Another area in development is Impact management and measurement (IMM) which seeks to support the assessment of the systemic success of the investments. It seeks to elaborate on societal and environmental impacts in addition to financials returns. To address the polycrisis, Hofstetter (2024) suggested that funders’ evaluation processes should evolve to support system complexity: moving away from ticking boxes for individual Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to understanding the connections between them. For example, linking personal mobility to health promotion, or mental health to urban planning, can help us develop innovative place-based systemic solutions.

The event made me hopeful by introducing so many maturing initiatives that are collaboratively building the skills and capabilities of societal actors to tackle the wicked problems of our times. I also felt inspired that the work we are doing in the Laurea University of Applied Sciences in advancing systemically informed innovation management and ecosystem orchestration seems highly relevant and timely in relation to what is happening globally.

One of the main implications I would highlight from the summit’s “we have to innovate how we innovate” call to action to the work we are doing at Laurea includes shifting our focus from business, product and service innovation to systems innovation. As the activities of single actor, team or organisation will not suffice in dealing with the polycrisis, we need long-term partnerships between organisations. In my previous work I have highlighted that t is not enough for these partnerships to co-create solutions but also 1) identify shared challenges and embrace collaborative governance, 2) created shared and actionable knowledge and, reflecting Hofstetter’s ideas on systemic investing, 3) use hybrid funding and portfolio management to fund and lead the composition of innovation experiments or ecologies of solutions (Seppälä 2023).

About the author

M. Soc. Sci., M. Sci. (Economics), MA (Adult Education), MBA (Service Innovation and Design) Mikael Seppälä is an expert in systemic innovation management and ecosystems orchestration who works as a project manager at the Laurea University of Applied Sciences.

Sources

- Ferrigno, F., Crupi, A., Di Minin, A. & Ritala, P. 2023. 50+ years of R&D Management: a retrospective synthesis and new research trajectories. R&D Management 53:5, p. 900-926.

- Hostetter, D. 2020. Transformation Capital – Systemic Investing for Sustainability. White paper.

- Hostetter, D. 2024. Financing systems change. Presentation in panel with Dominic Hofstetter, Annika Sten Pärsson and Jimmy Westerback at Waves Summit 2024.

- Seppälä, M. 2023. Sociology and Ecosystems Orchestration – From exploring multiple perspectives to engaging them in sustainability practices. Laurea Journal.

- Waves Summit. 2024. Waves Summit – Forum For Changemakers. Kulttuuritalo, Helsinki 3-4.4.2024. WWW-page. Accessed 7.4.2024.

ChatGPT was used in writing of this article by summarizing event notes done by the author and enhancing the fluency of the English language. The author is responsible for the content.

The text of the article has been reviewed and refined for clarity after publication (21.11.2025).